BEE HIVE JUN 2023*

Santa Marta Arqueological Site, BCS – April 2022

The trip to the rock art site at Santa Martha was almost four years in the making. It all began in November 2018 at the Mulegé Expo when we met a family from Rancho El Aguajito I, one of the ranches in Santa Martha, who had come to town to advertise and sell their wares and encourage travelers to visit the rock art.

While looking at their leather work, taste testing their goat cheese (queso fresco) and sweets (chongos – cooked and sweetened chunks of curds and whey—dulce de leche and cajeta—both caramel sauces made with goat milk and sugar) we chatted about the area and I took detailed notes about the logistics of making an overnight trip to the most accessible site, El Palmarito.

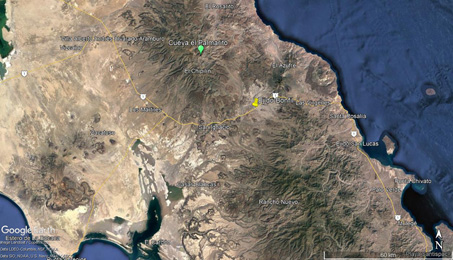

Regional map, showing Mulegé, Ejido Bonfil and the El Palmarito site. (Photo credit: Google Earth 2022)

Products from Rancho El Aguajito I in Santa Martha: (L to R) queso fresco, machacha (dry, shredded beef), empanadas (with sweetened queso, I think).

Souvenirs: mini teguas (traditional style leather hightop boots), can holders and other smaller craft items.

Embroidered kitchen towels, table clothes.

We know several people who have visited El Palmarito either on foot or mule, and they highly recommended it as a fun, fairly easy to modestly difficult day trip or overnight camping adventure.

With details and contact information in hand, we imagined a visit in 2020, with a friend of ours, my botany buddy/trusty assistant on my Mulegé Plant Project.

But then COVID-19 intervened.

We were gearing up in late March 2020 for our early April trip when I got a text from our contact that INAH (Instituto Nacional de Arqueología e Historia) had just shut down all archeological sites in the same way the federal government had shut down all beaches and parks and instituted a shelter-in-place order, mere weeks before

Semana Santa (Easter Week), the country’s most popular travel holiday, when those who can flock to the beaches or mountains to camp.

We ended up staying in Mulegé until mid May, enjoying the great weather and empty beaches, instead of returning to a San Francisco Bay Area that was full of sickness and freaking out, hoarding toilet paper and hand sanitizer. When we finally headed home, we had no idea when, or even if, we’d be able to return in the next year or two.

Fast forward to January 2022 and our arrival in Mulegé. I had been in touch with my contact in Santa Martha the previous summer when he texted to tell me they were open and suggested that October was an ideal month for a visit. I let him know we wouldn’t be able to visit until the upcoming April.

So now all together again in Mulegé, we made our preliminary plans for the upcoming adventure. Assuming, of course, that by that time I would have recovered enough from ankle surgery to be able to ride a mule and there were no other setbacks for any of us. We found an April weekend that fit in between vet clinic days for me and our friend’s return to the US for the summer. We added another friend to the party, one who was game for the mule trip, while my partner was going to forego the long (potentially very rough) dirt road and mule ride portion of the trip.

Day 1

April 8th finally arrived and, as bad luck would have it, it was the hottest day to date for 2022 in Mulegé. Our high temperature went up 10° from one day to the next and it was already in the high 80s (and rising) as we were leaving town at midday. And it only got worse: inland from Santa Rosalía we hit high winds, the dirt was filling the air and it was nearing 100° F. It did not improve much by the time we finally reached Santa Martha around 5 pm.

April 8th finally arrived and, as bad luck would have it, it was the hottest day to date for 2022 in Mulegé. Our high temperature went up 10° from one day to the next and it was already in the high 80s (and rising) as we were leaving town at midday. And it only got worse: inland from Santa Rosalía we hit high winds, the dirt was filling the air and it was nearing 100° F. It did not improve much by the time we finally reached Santa Martha around 5 pm.

But, I´m getting ahead of myself. Before we could even leave the highway to set off into the unknown, we first had to drop off my partner for the night at the Ecolodge near the base of Volcán de las Tres Vírgenes. The lodge is run by Ejido Bonfil as part of their big horn sheep hunting program. It is located about 1:20 hours north of Mulegé near the base of the volcano complex and has a breathtaking view of the mountains. It’s also very reasonably priced, ecofriendly and quite peaceful (except for the squeaky floor boards in the rooms and when the wind is howling!). Oscar and Maria are lovely hosts and promised to take good care of my partner while we went off on our adventure.

The road from Hwy 1 to the geothermal plant and the Ecolodge. Sign: "No littering".

The lodge is situated on the top of a low ridge and blends well into the desert scrub around it.

One of the eco-cabins with two separate rooms. The lodge is solar powered and has a recycling & composting program. Construction was designed to leave the smallest footprint possible within the scrub.

The view from one of the cabins, absolutely breathe taking.

Once we offloaded her, we hit the road for Ej. Bonfil, where just 15 minutes later we were filling up on cold drinks, searching in vain for some popsicles to cool us down and trying to stay upright in the strong, scorching wind. No luck, but we did buy some delicious, regionally grown medjool dates.

From the highway, just a few yards west of Bonfil, the 27 miles of dirt road to Santa Marta heads northwest for quite a way before swinging westward towards the base of the Sierra San Francisco mountains.

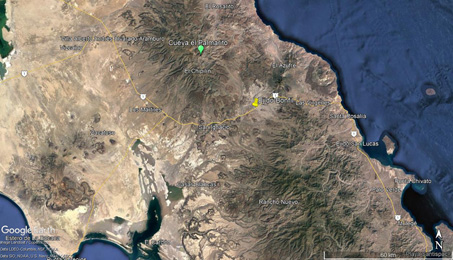

Map of the route we took from Ejido Bonfil to Santa Martha. The 27 mile trip from Hwy 1 took about an hour and a half. (Photo credit: Google Earth 2022)

Near Bonfil, a short stretch of pavement crosses a substantial arroyo. It was too hot to get out from the air conditioned truck for photos often, so I saved my strength for only really interesting plants/views.

The road was in excellent condition as it gradually climbed a small rise from an elevation of about 807 ft (246 m) to around 920 ft (280 m) and crossed a stark landscape of dark lava flows interlaced with pumice sand dunes. Our theory was that the pumice must have came first and then newer lava flowed, or was ejected, to cover deep beds of coarse pale pumice. No doubt, lighter grains of the sandy pumice are also carried across and deposited as dunes against the distant flows.

A look from near the top of the rise east towards the volcano complex.

Zooming in a bit, the white patches are likely a mixture of sand dunes and areas of gravelly pumice similar to where I was standing.

The vegetation in this region is typical of much of the peninsula´s desert scrub, though it is within the ecotone between the Central Gulf Coast and Vizcaíno ecoregions with fingers of vegetation coming in from the northernmost edge of the Sierra La Giganta ecoregion.

Another closer view of the volcano complex, behind a veil of dust/sand carried off the desert floor by the fierce, hot winds.

The ridge with mounds of smaller cinders and larger lava boulders were well-vegetated.

Species common to the three regions include: Creosote bush/Gobernadora (Larrea tridentata); legumininous trees like Littleleaf Palo Verde (Parkinsonia microphylla), Desert Ironwood (Olneya tesota) and Mesquite (Prosopis articulata); euphorbs like Candelilla (Euphorbia lomelii), Ashy Limberbush (Jatropha cinerea) and Limberbush (J. cuneata); cacti such as Cardón (Pachycereus pringlei), Galloping Cactus (Stenocereus gummosus), Organpipe cactus (S. thurberi var. thurberi), Old-man Cactus (Lophocereus schottii), Chainlink Cholla (Cylindropuntia cholla) and Peninsular Cholla (C. alcahes var. alcahes); the torchwoods species Red Elephant Tree /Torote Prieto (Bursera hindsiana) and Little-leaf Elephant Tree/Torote Colorado (B. microphylla); and Tree Ocotillo/Palo Adán (Fouquieria diguetii).

On the more open areas, the vegetation is widely spaced and the stark, bare pumice between the plants gives the landscape the look of a well-tended xeric garden, which it is, but just naturally created.

The wind, sun and insects are likely the primary "gardeners" here.

From near the top of the rise, a look back towards Ej. Bonfil.

Example of some of the larger pieces of pumice.

An impressive Cardón (Pachycereus pringlei) specimen.

Other species that are typical of the higher elevations of the Vizcaíno and of La Giganta ecoregions include: the leguminous Palo Verde (Parkinsonia praecox) and Palo Chino (Senegalia peninsularis); Baja California Elephant Tree/Copalquín (Pachycormus discolor); the local endemic San Francisco Agave/Maguey (Agave cerulata subsp. subcerulata); and Long-spine Cholla/Clavelina (Cylindropuntia molesta) and Prickly pear (Opuntia sp.).

Long-spined Cholla/Clavellina (Cylindropuntia molesta). There are a couple of varieties and hybrids of this endemic cactus but this is most likely the widespread var. molesta.

Those spines definitely say "keep back". The colorful flowers range from brownish-orange to wine red.

Something that really captured my attention along the road was the similarity in growth patterns of some of the dominant desert trees or shrubs. I was seeing the environmental influence on plant form in action. For example, around the lava flows/pumice fields Palo Adan, Little-leaf Elephant Tree and Palo Brea were growing alongside each other and all three species were for the most part very large trees (3-4 m H), with widespread, open, twisted and contorted limbs.

It seems logical that given the hot and arid environment where the soil albedo is very high (bright, blinding white to us) this type of branch architecture would: reduce UV exposure and reflection on different parts of the plant throughout the course of the day; improve air flow; and allow self-shading by the branches and leaves. The squat shape with distributed branches and their close proximity to other plants of similar size would also add to plant stability in these high wind areas.

Large specimens of Cardón, Little-leaf Elephant Tree, Organpipe Cactus and Palo Adán.

Blurry but cool: Little-leaf Elephant Tree.

I don’t know about you, but I find them to be quite beautiful and elegant in appearance, especially the green bark of the Palo Verdes and the golden peely bark of the Elephant Trees, and it was hard to take my eyes off of them as we drove along. Unfortunately, it was so hot and windy at the time that I didn’t get out of the air-conditioned car to take any photos of these beauties and so almost all of my photos from the moving car didn't come out well at all.

A blurry example of a Palo Brea (Parkinsonia praecox). You can get the idea of the spreading, contorted branches if you click to enlarge.

After about 20 minutes driving through the lava/sand dune area, the road descends into a wide, seemingly flat valley but there were twists and turns as we went into and out of small washes hidden by the dense growth.

Leaving the lava/pumice ridge and descending into a wide valley, the Llano del Gobernador ("Creosote Plain").

Going back down into another wash.

As the road continued northwest, the sides of the valley started to converge and we finally found ourselves in the bottom of Arroyo Santa Marta, a large canyon with the more vertical walls on our left formed by a stair step of volcanic mesas while on the right the walls looked more craggy like a bunch of lava had been thrown into a bunch of large, contiguous piles. The road followed the canyon, twisting and turning as it passed across and within the arroyo bed or skirted along on its bank.

Entering the canyon as the road arcs towards the west. The walls are getting closer.

Copalquín growing on the canyon walls.

The steep canyon walls were vegetated with tall, straight Elephant trees/Copalquín (Pachycormus discolor var. pubescens) which at the time were starting to turn yellow in preparation for shedding their leaves and blooming, perhaps later in the month or in May. Palo Adán (Fouquieria diguetii) showed a continuum from totally leafless to leafy with “pipecleaner” stems to bursting with flowers (with or without leaves); many of the inflorescences looked like scarlet pompoms at the branch tips.

Palo Adan blooms looking like scarlet pompoms (Fouquieria diguetii)

Inflorescences are typically more elongated like this, c. 15-20 cm L.

The stems of Peninsular Cholla/Cholla Barbuda (Cylindropuntia alcahes var. alcahes) were packed with clusters of 3-4 flowers all blooming together and many buds waiting their turn. There were also Prickly Pears (Opuntia sp.) with a few large and bright yellow flowers but with many buds ready to pop.

Palo Blanco (Lysiloma candidum), Palo Chino (Senegalia peninsularis) and Mezquite (Prosopis articulata) were also blooming, especially in the arroyo bottoms.

Peninsular Cholla/Cholla Barbuda (Cylindropuntia alcahes var. alcahes).

The flowers of Peninsular Cholla range from yellow to green to red (and any mix of those three) as you move through the species range.

An unidentified Pricklypear Cactus/Nopal (Opuntia sp.).

It was great to see a number of native bees working the flowers of this unidentified Pricklypear.

I was intrigued by all the shrubs with yellow or orange foliage (Parkinsonia microphylla and Parkinsonia praecox, Pachycormus discolor, Fouquieria diguetti, Pleradenaphora bilocularis and Jatropha cinerea) – it’s not fall colors that are spectacular here, but those of spring. It’s a time when many species shed their leaves as they bud and bloom. Others, like Fouquieria and Jatropha spp. put out leaves almost year round, whenever there is sufficient rain to kickstart their metabolism. They then shed them as soil moisture reaches some criticial threshold.

Dense vegetation in the arroyo bottom.

Palo Chino and Palo Verde in the bottom of an arroyo, their leaves starting to turn yellow.

As we weren’t really sure exactly where we were supposed to meet up with Patricio, the INAH rep, in Santa Martha and signage was not particularly helpful as we were driving, we decided to just stop at a ranch to ask directions. The first people we saw were at Rancho Las Sábilas. They assured us we were on the right road and that Santa Martha was maybe 20 minutes derecho (straight ahead, which is the common response to the location of almost anything, and which is not necessarily just straight ahead).

Approaching Rancho Las Sábilas.

Map of the Santa Martha area with the main road in red and the mule trip in green. (Photo credit: Google Earth 2022)

The road continued to zigzag along the rocky arroyo bottom, narrowing gradually and when we finally came upon a tiny sign in the middle of a fork in the road announcing “Santa Martha”, we were unclear if it was indicating to the left or right. The forks looked about equal in size and wear. We stayed right, not always a bad idea when unsure of where you are going, though sometimes it´s better to stay left….

Cerro el Pelón (Mt. Baldy!), located between las Sábilas and Santa Martha.

Sign #2.

About another 50 yards and another fork in the road with another small sign, this time on the left side of the road just a few feet after the fork. But, then to confuse our tired brains even more after almost two hours bouncing down a rough dirt road, when we looked a short distance down the right fork, a third, larger, government sign welcomed us to Santa Martha. ¡Híjole! Oh, come on!

Maybe the correct road?

Sign #3, just up the road from sign #2.

We finally ended our debate about which road to take and took the left fork, only to find that about 20 yards farther along that, the previous fork in the road joined it, and then carried us on a short distance to another modest, well-groomed ranch site with a lovely small vegetable garden and lots of flowers around the house.

Not seeing anyone, we kept driving but then decided to turn around and ask directions after we saw a young man coming out of one of the buildings. Omar “clarified” our confusion, stating that the entire area was referred to as Santa Martha or Rancho Santa Martha, and that we were currently at the eponymous rancho, his home. Making the whole issue even more confusing is that I hadn’t understood that while the ranchers we met several years ago at the Mulegé Expo had advertised their products as being from “Santa Martha”, they were actually from Rancho El Aguajito I, located maybe an hour away on a different road. Well, now that’s all clear…

Omar informed us that our INAH contact Patricio was in Vizcaíno but that he´d call him on the radio later to let Patricio know we´d arrived and would be camping about 500 yards up the road from his ranch. We learned that Patricio didn´t live at Rancho Santa Martha, but lived in Santa Martha at Rancho El Sauce. We were catching on.

Rancho Santa Martha.

Rancho Santa Martha.

Omar told us that we could basically camp anywhere we wanted, though he recommended the cancha just up the road from them, a small concrete slab with a smoothed out area around it that they used for dances and other community activities. We were within sight of the albergue, the boarding school for ranch kids from the region and a useful landmark.

We took Omar´s advice. Jagged volcanic mountains loomed up on all sides of us and their dense desert scrub came downhill to the the edge of the road and camp. As we set up our tents, we were very much on our own in what felt like the middle of nowhere. Well, technically it kind of was… Just us, the hot breeze, the twittering of birds in the bushes around the camp and the occasional sound of cows lowing in the distance.

From the topo map, this looks to be Sierra el Carricito to our south.

Sierra Carricito to the left of the V, Sierra la Higuera to the right.

At the edge of the road near our camp the scrub was often impenetrable. Chainlink cholla, Galloping cactus, Cardon, Lomboi and Frutilla.

Fruit & old flowers of Peninsular Barrel Cactus/Biznaga (Ferocactus peninsulae var. peninsulae).

Not long after we were settled, the heavy afternoon commute traffic trotted by: three vaqueros (two men and a boy) on mules, heading out to find a cow on the loose.

Thankfully, the night cooled off quickly and after a hearty meal and some chewing the fat around the flashlight, we all retired to our tents.

Rush hour traffic. Behind these friendly vaqueros is Sierra las Chivas and behind the mountains, tomorrow's rock art destination.

Sunset on the Sierra la Higuera.

The next traffic was at about 11 pm: Patricio and his family came bouncing up in their pickup truck on their return from a six hour roundtrip to Vizcaino to deliver their goat cheese to market.

They stopped to talk and Patricio and I clarified where and when we would meet in the morning to sign in and join the guide for our mule ride up to El Palmarito. About 10 minutes, derecho...as he pointed off into the dark night.

The night was very still and the stars were brilliant. The wind had calmed completely and the occasional gentle tinkling of cow or goat bells in the nearby scrub was reassuring in all that vast space. At one point in the night, I awoke to what I thought was at first a bad case of tinnitus, then what must be a swarm of monster-sized crickets. But I soon realized it was a “deafening” chorus of frogs. Frogs in the desert?? I suddenly remembered that Omar had suggested we might want to take a dip in the represa (dam) located about 50-75 yards from camp, but we had all been too tired after dinner to walk the short distance. There was some heavy action happening out there in the dark that night.

The real adventure begins on Day 2 > > >

* This entry was to appear in the Nov 2022 issue of the Beehive, but publication was delayed due to staffing issues.