BEE MAR 2015

The Good, The Bad, and The Prickly: Botanical Adventures in Baja California - Part 2

Last month I was invited to give a talk in Loreto about Baja California plants. In my last entry, I discussed plant species in general and two of the Sonoran desert subregions that encompass the area of Mulege and Loreto. In this installment I will expand on the "Good" and the "Bad" elements of my presentation.

The “Good” I am referring to includes the majority of the peninsula’s plants, basically those that don’t scratch, grab, poke, sting, irritate, poison or otherwise harm us or other organisms. They are often interesting or just plain gorgeous in their own right. I’m an equal-opportunity botanist, so I find it hard to vilify plants! I find even the prickliest, “meanest” plants to be beautiful, except precisely at the moment when – ouch! – they cease to be!

Drymaria holosteoides var. holosteoides (Caryophyllaceae). This endemic annual with a delicate flower is commonly found on saline soils near beaches and salt flats as well as hillsides near the coast.

Drymaria holosteoides var. holosteoides (Caryophyllaceae). This endemic annual with a delicate flower is commonly found on saline soils near beaches and salt flats as well as hillsides near the coast.

Canyon Snapdragon (Pseudorontium cyathiferum, Plantaginaceae) is another delicate annual, usually less than 40 cm tall.

Canyon Snapdragon (Pseudorontium cyathiferum, Plantaginaceae) is another delicate annual, usually less than 40 cm tall.

Hofmeisteria fasciculata var. pubescens is a perennial herb endemic to BCS, extending from around Santa Rosalía to at least Agua Verde. It blooms during the winter.

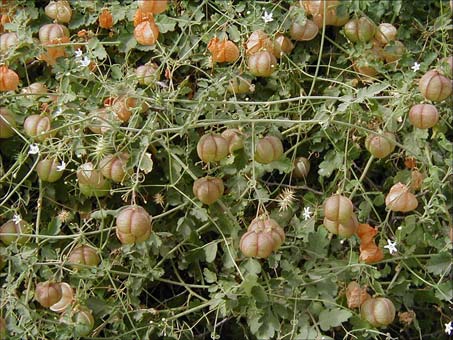

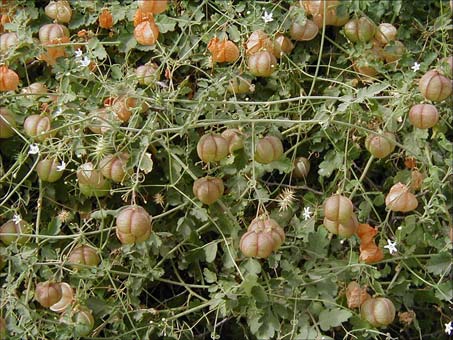

Coyote Melon or Calabacita de Coyote (Ibervillea sonorae, Cucurbitaceae). A perennial native vine. Fruits are supposed to be bitter, but the one I tried was sweet. More research needed...

Drymaria holosteoides var. holosteoides flowers are about 1 cm D. The herb spreads rapidly by above ground stolons and produces thousands of minute seeds.

The flowers of Canyon Snapdragon (Pseudorontium cyathiferum, Plantaginaceae) are about 5-7 mm W and one of my favorites.

The flowers of Canyon Snapdragon (Pseudorontium cyathiferum, Plantaginaceae) are about 5-7 mm W and one of my favorites.

These mini pompoms measure about 2 cm D and are on long pedicels that stick up well above the plant. They can be seen most often hanging off cliff faces and road cuts.

This species of Coyote Melon (Ibervillea sonorae) has a large, cement-like tuber for storing nutrients.

Vines are very common in the desert after good summer rains. Their form is a highly adaptive structure for living in the desert. This growth form allows the plants to use the shade and structure of other plants and also places the herbage well above the ground surface, which can be much hotter than just a few inches above the soil. Some vines, like Brandegea bigelovii or Vaseyanthus insularis will form such dense bowers on top of other shrubs that the underlying plant becomes obscured.

Desert Starvine (Brandegea bigelovii, Cucurbitaceae) in the Mulegé Valley in the months after Hurricane Jimena (2009).

Tronadora (Cardiospermum corindum, Sapindaceae) is another interesting perennial vine with papery capsules.

Desert Starvine persisted in the Mulegé Valley for a number of years after Jimena. I see a horse and jockey in the natural topiary...

Flowers and fruit of Tronadora. When dry, they often fall off and tumble away, breaking open eventually to spread the seeds.

Edible plants

There really isn't much out there most of the year that is palatable to humans. Almost all of the cactus fruit, with the exception of the dry and fibrous fruits of the Cylindropuntia, are juicy and edible when raw, while the flesh of the cacti themselves are not so much, and can cause intestinal upset in quantity. They can be cooked with a better outcome.

A great number of plants have dry fruits or very small fleshy fruits, only some of which are edible for humans or even worth the time spent collecting them. The young leaves of some herbs, such as Amaranthus, Portulaca oleracea and Dysphania ambrosioides can be used as pot herbs. The native species of figs (Ficus spp.) and palms (Washingtonia robusta and Brahea brandegeei) offer only tiny, dry fruits. On the other hand, birds and rodents have much to choose from.

The young leaves of Dysphania ambrosioides (Chenopodiaceae), known as Epazote in Mexico, are used to flavor a number of dishes.

The dry fruits of Mexican Fan Palm (Washingtonia robusta, Aracaceae).

Parasitic plants

Then there are those plants that are harmful to other plants and to us as well which, those that could be called "bad". These include parasites, invasive, and noxious species.

Parasitic usually can’t make their own food from the sun (they generally lack chlorophyll) so they steal sugars, water and/or other nutrients from their host plant. Some species do have chlorophyll and primarily steal their host´s water.

In our area, there are several parasitic plants that seem to thrive without killing their hosts outright. These are from three families and three genera. Mistletoes are represented by Phoradendron californicum (Viscaceae)—which parasitizes leguminous trees, primarily Mesquite (Prosopis spp.), Desert Ironwood (Olneya tesota) and Palo Verde (Parkinsonia spp.)—and Psittacanthus sonorae (Loranthaceae) which is found on Elephant trees (Bursera spp.) in our area. Both of these species attach themselves via specialized structures called haustoria that penetrate the bark. Their juicy fruits are attractive to birds and the sticky seeds are later excreted, perhaps while the bird is perched on a new branch. If the branch is of the correct species, the seedlings roots will begin to do their job of attaching itself to the host. The stems of Psittacanthus blend so well with the bark of Bursera hindsiana that it is often difficult to see the junction when both plants are dormant.

Sonoran Mistletoe o Toji (Psittacanthus sonorae) on Torote Colorado (Bursera microphylla). This species usually blooms in the cooler months (Dec. to Feb.). Clusters range from about 15-60 cm D.

The flowers of Toji lack petals, but the 6 sepals are each about 1.5 cm long and the tube you see uncoils as they open. Hummingbirds and butterflies are common visitors. A native, desert species.

Dodder is another type of parasite, an annual that usually parasitizes annual or perennial herbs, at least in our area. Cuscuta tuberculata and Cuscuta umbellata var. reflexa are the two most common here. I have found the first on Bajacalia crassifolia (a small shrub with succulent leaves), Amaranthus and Boerhavia species while the latter is most common on Euphorbia polycarpa and Amaranthus watsonii. These species have bright orange, threadlike stems that twine and climb over the host plants. Especially in the case of Euphorbia polycarpa, a prostrate “sandmat”, there is often more parasite visible than host. Both species have minute white flowers and several tiny, rounded, sticky seeds.

From a course on plant “senses” that I took recently, I learned that Cuscuta species locate their host plants by means of the hosts´ chemical signature, volatile substances they excrete and the Cuscuta can detect.

Disturbed area covered in sand mat (Euphorbia polycarpa) which in turn is covered with dodder (Cuscuta umbellata var. reflexa).

Dodder on E. polycarpa (green leaves & red stems). The flowers are about 5-6 mm D. A native, desert species.

Invasive Plants

When we talk about invasive species, we may often be thinking about animals that have been introduced into an area that then run wild. However, introduced, or “exotic” plants that have been introduced into new areas can also become invasive and destructive to the natural environment.

As I've mentioned in past posts, here in Baja California there are a lot  of free ranging goats, cattle, mules, and horses that have changed the appearance of the desert environment, trampling sensitive areas and eating the tasty native plants while avoiding less palatable species. These exotic animals, together with other human activities, are acting as vectors for the unchecked spread of some exotic plant species and as the catalysts for an ecological imbalance.

of free ranging goats, cattle, mules, and horses that have changed the appearance of the desert environment, trampling sensitive areas and eating the tasty native plants while avoiding less palatable species. These exotic animals, together with other human activities, are acting as vectors for the unchecked spread of some exotic plant species and as the catalysts for an ecological imbalance.

Buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare, Poaceae) is a perfect example of a baaaaad plant. A native of arid Africa, it was introduced into the Southwest US and Northwest Mexico as cattle forage with disastrous results. Domestic cattle in North America which did not evolve with this grass find the prickly heads unpalatable and will not eat it. As the plant continued to spread after its introduction, it went unchecked and covered huge areas of desert. It is now becoming a major invasive species here in Baja California where it can be found throughout much of the peninsula along artificial corridors such as roads and livestock trails. The main problem with this species is that it is so well-adapted to the aridity and goes mostly ungrazed that it is able to proliferate freely and rapidly much of the year. It out-competes the more delicate, native annual and perennial grasses that are tuned in to seasonal growth patterns. With its prolific biomass, Buffelgrass also poses a fire risk in an ecosystem that is not at all fire adapted.

Buffelgrass rapidly colonizes disturbed roadside real estate and chokes out other native species.

Buffelgrass on the left and the shorter, more delicate native grasses in the center.

Giant Reed or Carrizo (Arundo donax, Poaceae) poses a similar threat, rapidly taking over waterways and choking out other slower growing native species of reeds and grasses. It too poses a fire hazard, and often grows along side palm trees that also pose a great fire risk, especially where humans are involved. After fires or flood damage, it returns in even stronger force. This plant does provide some benefits however, in that it creates wildlife habitat, especially for birds and small mammals around otherwise exposed waterholes, and in some communities it is of economic importance as an artisanal construction material.

Giant Reed (Carrizo) growing along the bank of the Mulegé River. It can reach 5 meters or more in height and grows primarily by rhizomes rather than seed from the showy, feathery inflorescence.

Crystalline Iceplant (Hielitos, Mesembryanthemum crystallinum, Aizoaceae) is another pesky non-native, originally from Africa. It can carpet an area and choke out almost all other plants.

Another roadside invasive, this time from Europe, Goathead (Toritos, Tribulus terrestris, Zygophyllaceae) is spread along the edge of the highway by tires and is also found in driveways and gardens.

The split, flattened and dried stalks (culms) are woven into mats called petates that can be used as walls and windbreaks, here creating a spiral stall for our composting toilet.

The succulent leaves of the annual Crystalline Iceplant is covered with tiny vesicles (inflated hairs) that are filled with salty liquid, acting to sequester salts that can damage its tissues.

Goathead also belongs in the prickly section. Its fruit has 5 sections that break apart. Each has sharp, hard spines that stick deep into tires and shoes and feet of all species, aiding in its dispersal into disturbed areas.

Hey, you're irritating me!

There are a number of plants that have stinging hairs, poisonous sap or some type of irritating exudate or covering. I remember in the early days of my plant explorations in Baja, I came across a plant that I handled extensively as I photographed, collected and examined it further under the microscope. Only later, once I had identified it, did I learn that it can often cause contact dermatitis! Fortunately for me, I did not suffer for my ignorance.

Plants that have a sticky, poisonous and perhaps irritating (to some) latexy sap include: several species in the Euphorbia family, such as Euphorbia ceroderma, E. lomelii, E. magdalena, and E. polycarpa; and a number of species in the Dogbane family (Apocynaceae) such as the milkweeds Asclepias albicans and A. subulata; India Rubbervine or Cuernos (Cryptostegia grandiflora), Climbing Milkweed Funastrum cynanchoides subsp. hartwegii), Milkvine or Talayote (Matelea spp.), and Seutera palmeri. The finely chopped branches of Arrow Poison Plant (Sebastiania biloculare, Euphorbiaceae) were purportedly used by native people on the peninsula to make a concoction to stun fish.

I take care with all of these plants in that I try not to rub my eyes or put my fingers in my mouth or nose until I wash my hands, and avoid getting any camera parts gummed up with their sap. So far, I´m still kicking, and I suffered no stunning effects from just touching (and collecting) the Arrow Poison Plant, as a local once warned me not to do…

Seutera palmeri is a delicate, twining vine often forming gray-green mantles. The white patches are the ripe seeds emerging.

The ripe fruit of Seutera palmeri. Like most milkweeds, its seeds have a silky coma that lofts them far and wide.

The yellowish-green flowers of Seutera palmeri are about 5-7 mm D, and occur singly or in clusters as above.

Climbing milkweed (Funastrum cynanchoides subsp. hartwegii, Apocynaceae)

Finally, I should mention that there are a few really unpleasant species when it comes to flavor. Two species that I know well both carry a "bitter" warning in their common Spanish names: Calabacita amarga or Coyote Melon (Cucurbita cordata, Cucurbitaceae) and Palo Amargoso (Castela polyandra, Simaroubaceae). Take it from me, you will regret testing their bitterness…

Coyote Melon, or Calabacita amarga (Cucurbita cordata) has small melons measuring about 8 cm D. The fruit is very bitter.

I did warn her!

Well, that’s it for this month. Next time, I’ll tackle a spiny subject in the final installment of “The Good, the Bad, and The Prickly.”

Until then, hasta la próxima…

Debra Valov—Curatorial volunteer