Cueva San Borjitas, BCS.

Hidden in deep, isolated canyons of the sierras of the Baja California peninsula, prehistoric cave art records the history of the area's prehistoric, nomadic tribes. Carved into or painted on rock faces, cave walls and overhangs are simple images of the heavens, or often larger-than-life images of animals and people. The rock art is currently undergoing intense study to determine its age. Its meaning and purpose can only be surmised.

Many small ranches still exist in the rugged mountains of Baja California. Many families date back to the original Californios, those who worked for the missionaries but stayed to settle in Baja when the missionaries left.

In this section, you will learn more about Baja's cave art, how these artworks are being protected and how to visit the sites. You can also read about life on the ranches in an article written by Trudi Angell especially for this class topic.

You'll find links to the class handouts used at ISSI (Intensive Spanish Summer Institute) here and in the ISSI archives. You can also link here to the vocabulary list for this topic or see the Spanish translation by clicking on individual red words in the text below.

The cave art of the Baja California peninsula represents one of the most important collections of prehistoric art in the world and is considered to be on a par with the neolithic art of Europe and Africa. Art styles range from petroglyphs engraved on basalt boulders with simple designs (geometric symbols) or complex images (animal or human figures) to gigantic painted murals tucked away in rocky overhangs and shallow caves and depicting hundreds of human and animal figures. Much of the art across the peninsula shares a common, underlying theme, though execution and style can vary regionally.

Agua Fria Ib

Copyright © Harry Crosby

Until 2000, it was believed that the cave paintings, or pinturas rupestres, of Baja California were only about 1,900 years old. However, radiocarbon dating of the pigment binders were completed in 2002 and show that the paintings of San Borjitas cave, near Mulegé, may be about 7,500 years old (5400 A.C.), making them perhaps the oldest North American rock art known. However, there continues to be some dispute about the methodology involved in the study and its validity. Read an article on the details of various methods used at different rock art sites over time.

Much speculation exists about the people who created the cave art. Francisco Javier Clavigero was one of the first to describe the paintings in his book A History of Baja California published in 1789. He writes that when the Spanish Jesuit missionaries were establishing missions on the southern peninsula at San Ignacio and Santa Gertrudis in the early 18th Century, they heard stories from the native Cochimí about a race of giants from the north who had inhabited the land long before them and who had painted the gigantic murals. They claimed to be unrelated to this tribe and denied knowledge of their meaning.

Most likely, the artists were members of the now extinct Pericú (south), Guaycura (central) and Cochimí (central & north), indigenous nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes who exploited the region’s resources, migrating seasonally between sea and mountains in search of food, water and shelter and leaving their mark on the cliff faces and rock shelters close to their seasonal campsites. Unfortunately, no other archeological finds exist that help to explain the true significance of the cave paintings.

Historical Research

The first scientific documentation of cave art on the peninsula was made in 1883 by Herman Ten Kate, a dutch, and Lyman Belding, a north american naturalist. Leon Diguet, a french chemical engineer, first came to Baja California in 1889, having been contracted by the Boleo mining company in Santa Rosalía to survey for copper deposits. By the time he left Baja in 1892, he had written a number of scientific papers, including several on the subjects of local anthropology and archeology. He later returned to Baja California, this time as director of French expeditions in Mexico and led four expeditions beginning in 1894. In his published articles, he described in detail the art and artifacts of at least thirty different sites, and distinguished between two types of rock art present: petroglyphs and cave paintings.

After World War II, interest in the peninsula’s prehistoric past began to increase. William C. Massey, an archeologist from the US, was one of several to explore the peninsula’s archeological sites. In 1949, the first expedition to be backed and led by Mexican scientists was undertaken by Fernando Jordán, Barbro Dahlgren and Javier Romero. They traveled to San Borjitas, near Mulegé in the Sierra Guadalupe. Jordán extensively photographed the paintings, Dahlgren created careful drawings of the figures and Javier Romero excavated the surrounding area, where he discovered a number of stone artifacts (grinding stones or metates). Their published work brought the cave paintings into the national spotlight.

Erle Stanley Gardner, escritor de las novelas de misterio y aventurero, comenzó a explorar la península de Baja California en 1961, llevándo consigo en sus diversos viajes a los científicos más conocidos de la época. En 1965, fue acompañado por el Dr. Clement Meighan de UCLA. Se le atribuye a Meighan el primer estudio científico riguroso del arte rupestre de la región y elevar el nivel de interés y discurso sobre la obra de arte y su importancia.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, photographers Harry Crosby from San Diego and Enrique Hambleton from La Paz, together traveled about 600 miles on mule and horseback, exploring an area of more than 7,450 sq. miles of rugged country where they photographed, documented and lent interpretation to more than 200 rock art sites, many of them never seen before by outsiders. Their subsequent work, The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People, first published in 1975 and later updated in 1997, continues to be the definitive work in English on the subject and made accessible to a greater public the beauty and mystery of this art form.

The Art

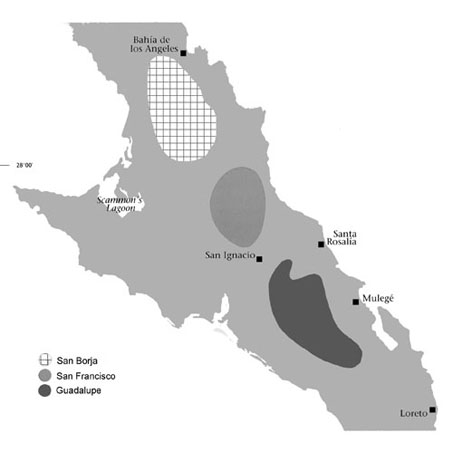

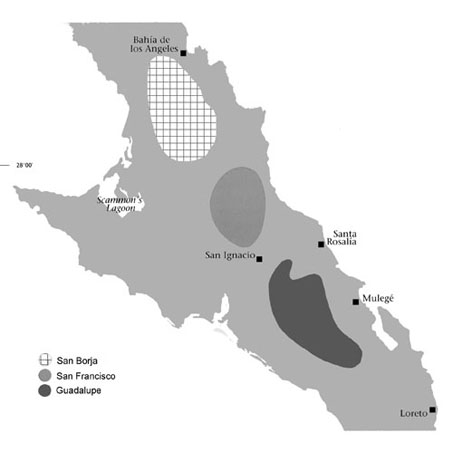

While there are a number of styles of rock art throughout the peninsula, perhaps the best known and most studied is that of The Great Mural style. Over 1200 known sites with paintings of this style occur in the central region of the peninsula, including the Sierra San Borja, Sierra San Francisco, and Sierra Guadalupe (see map).

The art has been carried out on a monumental scale. Some sites have hundreds of figures, many of them overlapping and that can reach high up on the cave walls or on rock overhangs. Figures are executed with a high level of skill as compared to art of other areas of the peninsula..

Map source: adapted from Crosby (1997) and Gutiérrez Martínez (2003)

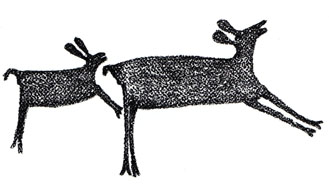

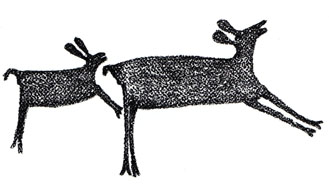

Deer, rat and human figures, La Cueva del Ratón. Note overlapping figures. Sierra San Francisco

While there are five recognized sub-styles of the Great Mural art demonstrating distinct differences in how figures are depicted—realistic versus abstract images; images filled with one or more colors versus unfilled images; anthropomorphic figures with disproportionate body sizes and square heads for example—the subject matter is fairly homogenous across its range.

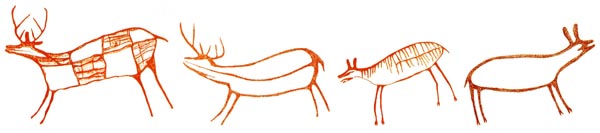

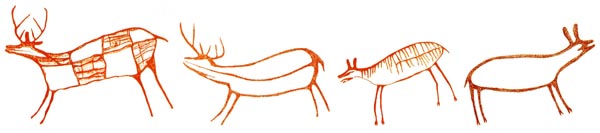

Different styles of deer across the Great Mural region (above)

and two drawings below Copyright © Harry Crosby

Depictions of wildlife are the most common, representing bighorn sheep, rabbits, jackrabbits (hares), mountain lions, deer (left) and turkey vultures.

Depictions of wildlife are the most common, representing bighorn sheep, rabbits, jackrabbits (hares), mountain lions, deer (left) and turkey vultures. Terrestrial animals often were shown with arrows piercing or lying across their bodies. Marine animals such as manta rays, fish, and turtles can also be found.

Terrestrial animals often were shown with arrows piercing or lying across their bodies. Marine animals such as manta rays, fish, and turtles can also be found.

Ranging anywhere from a few inches to more than ten feet, human figures, referred to as ‘monos’—men, women and what have been interpreted as shamans (human figures wearing odd head dresses— right) are also represented. Many of the images overlap others. Little is actually known about the nature of the symbolism of the figures or the use of colors, where ochre, black and red predominate and only a small amount of both white and yellow is used.

More is understood about the process by which the art was made. Pigments were created from ground minerals from local rocks, bound together with water and cactus juice. It has been proposed that the paintings of the Great Mural style were created using scaffolds constructed from palm trunks that were tied together with ropes and cords made from plant fibers such as palm fronds or agave. Brushes were most likely fabricated from the fibers of the Maguey plant (Agave species) common to the area.

Much of the work is superimposed over previous layers indicating that the paintings were likely laid down over several hundred to thousands of years and therefore across many generations. This means that the Painters would have repeatedly returned to the same remote areas to engage in the act of painting—why, we will never really know. The paintings of the Great Mural style do show clear evidence of being repainted and retouched, especially on some of the human figures. It is thought that this may have been done because these images were particularly venerated, representing either mythic figures or their own ancestors. Earlier attempts at carbon dating of the images were skewed, giving an age of less than two thousand years, because while it was correctly surmised that the underlying images would be the first and therefore oldest, it was not initially known that many of these had been retouched hundreds or even thousands of years later.

Other styles of rock art are found in the northern peninsula. One well known example that is open to the public is El Vallecito, located about 42 miles east of Mexicali. It is considered to be the most representative of the region and six of the 18 sites at this location can be visited. Images include geometric and anthropomorphic figures, a shark’s head, a butterfly and a man apparently rooted in the ground (el hombre enraizado).

Conservation

Baja’s cave paintings are impermanent although they have so far persisted for hundreds or thousands of years. The paintings are exposed to the elements—rain, hurricanes, extreme heat and cold, and will eventually erode. Additionally, salts dissolved in the water undermine the underlying rock and painted layers, gradually loosening the pigments and layers of rock from the cave’s surface. They have managed to escape significant vandalism in recent times primarily because they are located in such remote areas that are not easily accessible.

Visitors to all cave painting sites are required to purchase permits from the local INAH office and contract registered guides in order to make trips to the individual sites. Throughout the peninsula, local people, such as ranchers, on whose land the paintings are to be found, are now charged with protecting these world treasures.

Access to the sites is controlled locally and most guides are usually from the area of the site, although outside groups registered with the government office can also lead trips in conjunction with local  custodians. This locally based stewardship program has improved the economic condition of surrounding communities and provides revenue for the ongoing protection of the artwork.

custodians. This locally based stewardship program has improved the economic condition of surrounding communities and provides revenue for the ongoing protection of the artwork.

In 1993, the Sierra San Francisco, and the rest of the surrounding Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. This area contains a large number of significant sites of the Great Mural style, and at least 350 registered sites. A management plan has been in place in the Sierra San Franciso since 1998, in which is laid out methods to help decrease the impact of public visits. Currently, many of the most heavily visited sites have handrails, walkways, paths, or protective fences and access is strictly controlled and monitored.

Bilingual interpretative signs at la Cueva del Ratón.

Visiting the Art

To truly enjoy the beauty of both the cave art and the surrounding desert areas, visitors should take the time to go on a mule trip adventure. Multiple-day trips down into the canyons of the Sierra San Francisco allow the visitor to visit numerous sites, such as the spectacular Cueva Pintada and Cueva de las Flechas in Santa Teresa Canyon.

Cañon de Santa Teresa, Sierra San Francisco

La Cueva Pintada, Cañon de Santa Teresa, Sierra San Francisco

Santa Martha, between Mulegé and San Ignacio also offers the chance of multi-day trips or a day-trip on foot or mule. For the traveler with limited time or some physical limitations, there are a number of sites that can be visited on a day hike or after a 1-2 hour car trip and a short (15 minutes) to medium (1-2 hour) walk. La Trinidad and Cueva San Borjitas outside of Mulegé are good examples, as is Cueva del Ratón in the Sierra San Francisco.

To arrange to visit the Sierra San Francisco or Santa Martha sites without a tour company, contact:

INAH (National Institute of Anthropology and History) en San Ignacio, BCS

- From the US, call 011-52-615-154-0222

Daily rates in pesos (aprox.):

- guide - $60 to $200 per group

- pack animals - $150 each

- permit - $35 per persona

- camera - $35 per camera

View of the Sierra San Francisco from Cueva del Ratón

Cave painting trips are also a great opportunity to get to experience a slice of ranchero life. Some families date back to the first Californios, settlers who arrived with the missionaries in the 18th Century but who stayed on after their departure and moved into the mountains to start isolated ranches. Traditional crafts such as leather working, embroidery, cheese making and animal husbandry are still actively pursued. Experience a slice of ranchero in this article written by Trudi Angell especially for this class topic. You can also read about a The Mula Mile, a 1000 mile trip up the back of the peninsula on muleback that Trudi, her daughter Olivia and several other women made between November 2013 and June 2014. Follow Olivia's blog from the beginning here. They visited the isolated ranches throughout the peninsula.

Referencias

- Antigüedad del arte rupestre de Baja California ( Dec 2002) INAH. Comunicado de prensa.

- Chronology, context and select rock art sites in central Baja California. (2011 ). Ritter, E.W., Gordon, B.C., Heath, M., and Heath, R. SCA Proceedings, Vol. 25. University of California, Berkeley.

- Corazon Vaquero/The Heart of the Cowboy: A Journey into California’s Final Frontier

- Crosby, Harry (1997). The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People. Sunbelt Publications.

- Gutiérrez Martínez, M. (2003). El estilo Gran Mural en la Sierra Guadalupe, BCS. Arqueología Mexicana. Vol XI, Núm 62, pp. 44-5

- Hambleton, E. (2003). Lienzos de Piedra. Arqueología Mexicana. Vol XI, Núm 62, pp. 46-51

- Pinturas rupestres más antiguas de America. (May 2008). INAH

- Reygadas Dahl, F. (2003). Historia de la arqueología de Baja California. Arqueología Mexicana. Vol XI, Núm 62, pp. 32-9

Links

Read more

Article on baja paintings by Mark Rose

El Vallecito (short description en español)

Sierra de San Francisco (Site by ProNatura)

"Todo sobre las pinturas..." Article in Spanish from México Desconocido magazine

"Una ruta de arte rupestre en Baja California" (article in Spanish from México Desconocido magazine on northern art)

Bilingual blog of the Mula Mil journey by mule (2013-14)

Service providers / Proveedores de Servicios

Casa Leree Bookstore

Ecoturismo Kuyimá (rock art tours and

whale watching

based in San Ignacio)

Ignacio Springs B&B (yurts)

Mulegé Tours (La Trinidad & San Patricio sites)

Tour Baja (for caves, see Saddling South pages)

Terrestrial animals often were shown with

Terrestrial animals often were shown with