This essay was written especially for Las Ecomujeres and the ISSI course "Cave paintings and cowboys of Baja California."

Copyright © 2009 Trudi Angell & lasecomujeres.org

Imagine climbing up into your bunk for the night under a thatched roof on a bed of woven strands of leather you strung across a palm-wood frame. The stars light the dirt clearing between you and the corrals. There are no walls. You want the breeze to pass through to cool you at night. You’re up on the higher level so that animals of the night don’t disturb you, and on a sleeping pad below, also raised off the ground, is your dog. If a puma comes into your yard to kill the goats, the dog will jump down, you’ll wake up, touch the rifle at your side, listen closely to the night sounds and try to sense if the goats are disturbed.

Imagine climbing up into your bunk for the night under a thatched roof on a bed of woven strands of leather you strung across a palm-wood frame. The stars light the dirt clearing between you and the corrals. There are no walls. You want the breeze to pass through to cool you at night. You’re up on the higher level so that animals of the night don’t disturb you, and on a sleeping pad below, also raised off the ground, is your dog. If a puma comes into your yard to kill the goats, the dog will jump down, you’ll wake up, touch the rifle at your side, listen closely to the night sounds and try to sense if the goats are disturbed.

The goats are your livelihood and each one the puma takes is a week's worth of food lost to you. Food, and town, is a five-hour hike on old missionary trails from 300 years ago, cross-country through a treeless desert to a tiny oasis village, with one store. You go there every couple of weeks just so your tongue doesn’t get stuck to the roof of your mouth. You’ve never heard of Rube Goldberg but you’ve designed the perfect alarm system; cause and effect. And though your dog doesn’t talk much, he’s your best pal.

The goats are your livelihood and each one the puma takes is a week's worth of food lost to you. Food, and town, is a five-hour hike on old missionary trails from 300 years ago, cross-country through a treeless desert to a tiny oasis village, with one store. You go there every couple of weeks just so your tongue doesn’t get stuck to the roof of your mouth. You’ve never heard of Rube Goldberg but you’ve designed the perfect alarm system; cause and effect. And though your dog doesn’t talk much, he’s your best pal.

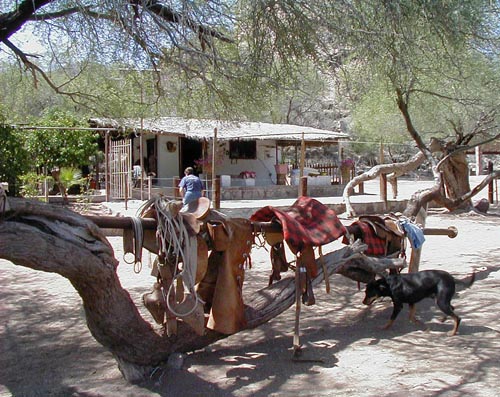

In Baja there are small isolated ranches, so close, and yet a world away from our everyday lives. Fifty-something Salvadór Meza lives alone, with his dog, in the Sierra de la Giganta two hours by car and four hours by mule from the bustling tourist town of Loreto. He prefers to hike rather than ride, a rare thing for a rancher here, and the village of Comondú is his main shopping destination. His sisters live there too, so when he wants some conversation he slings a leather bag over his shoulder and heads out.

In Baja there are small isolated ranches, so close, and yet a world away from our everyday lives. Fifty-something Salvadór Meza lives alone, with his dog, in the Sierra de la Giganta two hours by car and four hours by mule from the bustling tourist town of Loreto. He prefers to hike rather than ride, a rare thing for a rancher here, and the village of Comondú is his main shopping destination. His sisters live there too, so when he wants some conversation he slings a leather bag over his shoulder and heads out.

Just 40 years ago if you drove a few days south of Ensenada, as the highway turned to tracks through the cactus slopes, you’d see that remote ranches sprinkled sparingly through the desert had their own main roads. They were accessed by caminos de herradura (horseshoe trails) and it was a common sight to see ranchers riding into town on mules with a pack string of burros being herded ahead of the arriero (herder/wrangler). Cars and trucks were scarce back then.

Just 40 years ago if you drove a few days south of Ensenada, as the highway turned to tracks through the cactus slopes, you’d see that remote ranches sprinkled sparingly through the desert had their own main roads. They were accessed by caminos de herradura (horseshoe trails) and it was a common sight to see ranchers riding into town on mules with a pack string of burros being herded ahead of the arriero (herder/wrangler). Cars and trucks were scarce back then.

In the 21st century, there are still pockets of isolated roadless rancherías (small enclaves of a few families) or sometimes a paraje (single camp that offers seasonal grazing), but they are few and far between. In the upper reaches of Baja California Sur, in the Sierra San Francisco, more than a dozen are tucked into inaccessible canyons or perched high on volcanic ridges. A few are spread out over the hundred mile length of the Guadalupe Mountains southward to La Purísima. And in the Sierra Giganta, between Comondú and La Paz, Salvador Meza’s remote ranch is one of only ten or so in a mountain range that has been scribed and carved with dirt roads to make it easier for the locals to get their livestock to town.

In the 21st century, there are still pockets of isolated roadless rancherías (small enclaves of a few families) or sometimes a paraje (single camp that offers seasonal grazing), but they are few and far between. In the upper reaches of Baja California Sur, in the Sierra San Francisco, more than a dozen are tucked into inaccessible canyons or perched high on volcanic ridges. A few are spread out over the hundred mile length of the Guadalupe Mountains southward to La Purísima. And in the Sierra Giganta, between Comondú and La Paz, Salvador Meza’s remote ranch is one of only ten or so in a mountain range that has been scribed and carved with dirt roads to make it easier for the locals to get their livestock to town.

Many abandoned ranches are noted on detailed topographic maps that the statistic department updates on occasion. But prior to pavement and roads, those were working ranches and they formed a web of connectedness between families, trade routes and waterholes. Today along the Baja highways you rarely see those long-eared burros in a pack train, trotting ahead of a cowboy who needs to make a shopping trip!

Many abandoned ranches are noted on detailed topographic maps that the statistic department updates on occasion. But prior to pavement and roads, those were working ranches and they formed a web of connectedness between families, trade routes and waterholes. Today along the Baja highways you rarely see those long-eared burros in a pack train, trotting ahead of a cowboy who needs to make a shopping trip!

More vocabulary related to ranch life and cowboys can be found here.

Trudi Angell was born in Alta California and migrated to Baja California Sur in the mid 70s. First attracted to the peninsula as a sea kayaker, she spent a number of seasons exploring the coast of the Gulf of California between Mulegé and La Paz. Subsequently she began the first adventure tour company in Loreto, and over the years has logged more than 3000 sea miles by paddle and sail. In1986 she visited the mural rock art sites by mule with local cowboys of the region, went home to Loreto, bought a horse, and began to explore the canyons and ridges of the major sierras of the peninsula. Now with 3000 miles of trail riding under her sombrero as well, she is recognized as an authority on ranch culture of Baja. Two highlights for Trudi have been: a 41-day mule pack trip with her 9 year old daughter in 1999 from central Baja to the Sierra San Pedro Mártir following sections of the historic El Camino Real; and co-producing the film Corazón Vaquero in 2006, a documentary on ranch life of the peninsula. She and Olivia completed a 3-leg, 1000 mile trip up the back of the peninsula on muleback between November 2013 and June 2014. Follow Olivia's blog from the beginning here.

Trudi Angell was born in Alta California and migrated to Baja California Sur in the mid 70s. First attracted to the peninsula as a sea kayaker, she spent a number of seasons exploring the coast of the Gulf of California between Mulegé and La Paz. Subsequently she began the first adventure tour company in Loreto, and over the years has logged more than 3000 sea miles by paddle and sail. In1986 she visited the mural rock art sites by mule with local cowboys of the region, went home to Loreto, bought a horse, and began to explore the canyons and ridges of the major sierras of the peninsula. Now with 3000 miles of trail riding under her sombrero as well, she is recognized as an authority on ranch culture of Baja. Two highlights for Trudi have been: a 41-day mule pack trip with her 9 year old daughter in 1999 from central Baja to the Sierra San Pedro Mártir following sections of the historic El Camino Real; and co-producing the film Corazón Vaquero in 2006, a documentary on ranch life of the peninsula. She and Olivia completed a 3-leg, 1000 mile trip up the back of the peninsula on muleback between November 2013 and June 2014. Follow Olivia's blog from the beginning here.