FEBRUARY BEE 2014

Isla Coyote — Making a Plant Checklist

Isla Coyote – December 2013

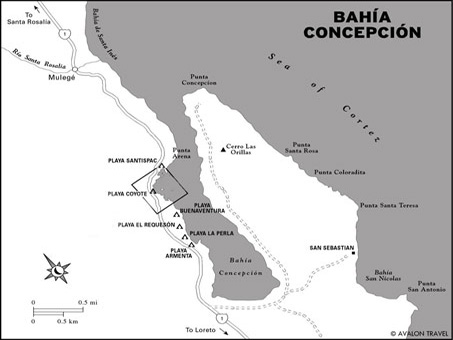

The things I get myself into sometimes for the love of plants! A friend invited my partner and I out in his catamaran to sail over to Isla Coyote, a small island in Bahía Concepción. We had originally met on one of my plant walks and now whenever we run into each other, he´ll tell me about the new and interesting plants that he's seen while hiking, and ask me about their names and properties. He´d said that he'd seen some really different plants on Coyote Island, that it was quite green after the summer rains, and that he´d like to take us out there soon. Having never been there and always having wanted to visit the island, we were eager to go. Chances like that don´t often come around twice.

We had a couple of false starts due to high winds. But the day we finally agreed upon turned out to be perfect for botanizing, but not so great for sailing (but I´d take plants over sailing any day!). We ended up motoring over to the island because there was not a breath of wind. The bay was glassy, it was slightly overcast and at 8 a.m., the temperature was pleasant. The water and sky were so beautiful and our time on the water as we crossed over to the island was very quiet, even with the cat's small motor puttering along.

View of Playa El Coyote and Isla Coyote, the large lump on the right side, in the middle of the image.

Leaving from Playa El Burro for the island. It was warm and calm and the water temperature was perfect for swimming.

Rounding the point and coming in towards the beach on the north shore of the island.

Approaching the beach. Beach grass on the berm with salt/mud flat behind and cliffs rising above to the island's saddle maybe 15-20 meters (or 48 to 65 ft) high.

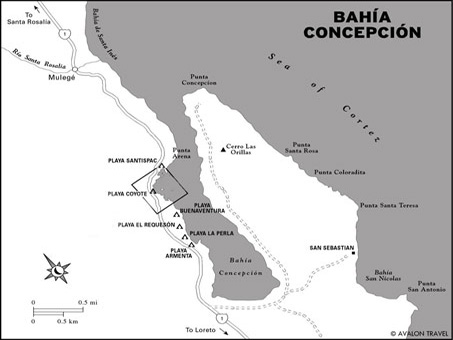

Isla Coyote is the small white dot in the center of the black square. Image from Internet.

Coyote Island is just to the left of center in this image, about 1/2 mile or so off shore.

The island is composed of volcanic lavas of various consistencies. It is well vegetated, except on the most sheer cliffs. Beach ahead with saddle above it.

Beach dune community with steep cliffs rising sharply out of the water.

When we got to the island and debarked, first onto the dinghy and then onto shore, the clouds were already starting to thin out, and the temperature and humidity climbed as the sun began to break through. The clouds of mosquitos that met us were very welcoming!

We landed on the north shore of the island, where there is a lovely crescent of white sand beach backed by a strip of mudflat (dry) with plants typical for that habitat: Iodine bush, Seablite, Boxthorn, Beach Dropseed and Sea Purselane (Allenrolfea occidentalis, Suaeda nigra, Lycium brevipes, Sporobolus virginicus, and Sesuvium portulacastrum). I wandered a bit, taking in the terrain, slapping at mosquitos, and dousing myself with repellant as I noted the vegetation. However, when I looked up at the cliffs behind the saltflat, my reaction was, "there is no way I'm climbing up that". I'm actually not too bad at going up, but coming down is a completely different matter and I didn't fancy slipping and sliding down the scree or off of a cliff on the way down.

Going against my better judgement, I listened as my friend assured me that there was a fairly easy path up the slope and I wouldn't have any problem. Sure, I said. I could see that he really didn't understand my physical issues. But then, there we were, in the middle of the bay on an island I´d always wanted to visit, the day was perfect (no wind), and was I going to back down now? Well...for the sake of botany...

He made several trial attempts without me, looking for a good path through the dense foliage. After about ten minutes, he'd finally decided on the best way up, one that traversed the face of the slope/cliff rather than going straight up it. "What am I thinking?" I asked myself not for the last time as I started up the "trail" after him, my walking stick clutched in one hand, the camera and water in my fanny pack. "I must be crazy," I muttered under my breath.

A good view of the crumbly volcanic rock surface. At least here, we weren't battling the spiny or sticky bushes trying to get us elsewhere. Just that loose scree...

As I was climbing and later going back down, I felt a close kinship with plants like these that are clinging for their lives to the cliff faces. This is a lovely Matacora, Limberbush (Jatropha cuneata, Euphorbiaceae).

Drymaria debilis (Caryophyllaceae), a delicate, annual, endemic herb that seems to especially like shady niches on rocky outcrops and canyon bottoms.

On the last ledge before the top.

A little more than half way up the hill. The vegetation was so dense in places, I was afraid it would bounce back and knock me down the hill.

An endemic, Pega pega (Eucnide aurea) is named for its ability to really stick (pegar) to things. It's more prickly and irritating than its endemic cousin Pegaropa (Mentzelia adhaerens Loasaceae) which acts like velcro, even sticking painlessly to skin!

The flowers of Drymaria debilis are scarcely 4-5 mm in diameter, and each petal is lobed twice. The stems and leaves are slightly-glandular hairy and the plant is often encrusted with debris.

It's a long way down there. But such an amazing view.

We finally made it to the top of the saddle after about 30 minutes of climbing, with a few stops to reassess the best route up. I took advantage of those stops to catch my breath, remove plant matter from my hair, body, and socks, rest trembling and tense muscles, take photos, drink electrolyte, and admire the incredible view. Did I mention I have a "thing" about heights? I am most definitely an obsessed botanist.

Still not quite there.

On flatter ground near the top of the saddle.

In the photo above (left), the wand-like plant is a Palo Adán or White Tree Ocotillo (Fouquieria burragei, Fouquieriaceae). The flowers are white or tinged with pink. It is a BCS endemic and its range begins about 10 km north of Mulegé and continues disjunctly south to around La Paz. It is found on rocky slopes and rocky alluvial fans. The dried inflorescences at the tips are rusty in this image, creating the appearance that it has reddish flowers. From a distance, many people confuse the dried inflorescences of the three species of Fouquieria for flowers. Even when this species is in full bloom, the flowers high up on the branch tips are almost invisible from a distance when against a light sky.

I was amazed how dense the plants were in some places at the top of the saddle. The bushes were thick with leaves and there was a lot of ground cover as well in the spaces between shrubs. The dominant plant was Matacora (Limberbush, photo above right, in foreground).

Palo Adán or White tree ocotillo (Fouquieria burragei, Fouquieriaceae). Some of these flowers have a faint tinge of pink.

Fagonbush (Fagonia barclayana, Zygophyllaceae), a low, prickly, endemic, perennial herb found mostly in rocky soils. This intricately branched, open plant is well adapted to the desert.

The trees and shrubs on the saddle were mostly short and rounded. There were both dense and wide-spaced areas like this.

Marina vetula (Fabaceae), a delicate annual herb. It seems to like open, rocky areas, such as on the saddle here.

Distinctly pink-flowered version of Palo Adán or White tree ocotillo. (Fouquieria burragei, Fouquieriaceae)

The prickliness comes from the four stipules. Usually they are fairly inconspicuous, but these were about 7-8 mm long and rigid. All parts except the leaves and petals are glandular-hairy.

The southern side of the island offers a lovely view and a sheer drop to the bay. Pitahaya agria (Stenocereus gummosus).

The inflorescences are about 5-8 cm L and erect to nodding. Flowers are pea-like, tiny (c. 3-5 mm L), and pale lavender or blue.

Plants up on the saddle show a distinct pruning effect due to the prevailing and often high winds that blow across the island from the north in Fall and Winter and from the south the other half of the year. Shrubs and trees, including Palo Adán, Palo Verde (Parkinsonia microphylla), Torote or Elephant Trees (Bursera hindsiana) and Brongniartia peninsularis (Fabaceae, a BCS endemic) were not much more than a 1.5 meter high and quite rounded. On the slope below the saddle, the Brongniartia and Palo Adáns were at least twice as tall and wandlike, their more common form in arroyo beds and plains.

We wandered around the saddle for awhile until my muscles were steady enough to head back down. However, just as we were starting the return trip, I walked into a Cholla cactus that was lurking under the leading edge of a Limberbush. Suddenly, I had three segments impaled in my kneecap and shin at multiple sites. Never one to panic, I calmly put down my fanny pack, extracted my clippers, and using the built-in digging prong, set right to work to detach the stems. By the time my friend returned with two flat rocks to help me (like tweezers), I had already yanked the last of the inch-long spines from my leg by hand and was ready to get down the hill before it really started hurting.

In spite of my trepidations about the difficulty of the descent, my friend found a shorter, easier way down than the one we'd ascended. We essentially walked down solid "steps" in the rock face, or in my case sat my way down! No slipping or sliding involved. In no time, we were safely back on the beach, and I was not only happy to be at sea level, but really glad that I´d taken on the challenge after all. Sweaty and hot, with the day having really warmed up, and the mosquitos zeroing in again for a meal, a dip in the bay was very welcome and soothing before we left the island.

We drifted around for awhile, with our friend rowing now and then, enjoying the dead calm water, the reflections and the wonderful clouds. Before turning back to the mainland, he started up the motor once again and we puttered around to the west side of the island, past some islotes (islets) that had a good deal of vegetation atop their rocky surfaces. It always amazes me how the desert plants can hang on so well in such a precarious environment and survive just a few feet above the bay and the salt spray.

What a lovely day on the Bay and on Isla Coyote! We had a great time, my leg was just a little worse for wear, but OK, and while I hurt everywhere for days after, valía la pena (it was worth the effort). During our hike, there was no way that I was going to try to deal with a notebook, so instead I pinched off tiny bits of every plant I came upon, a leaf here, a fruit there, and stuffed each piece into a plastic bag tied to my belt. When I got home and tallied up all of the plants and reviewed my photos, I was able to put together a list of 61 species in 23 families. The only plant that was new to me was a species of Dodder (Cuscuta sp., Convolvulaceae) growing on a dense mound of Frijolito (Phaseolus filiformis, Slimjim bean, Fabaceae).

The Making of a Checklist

Update Dec. 2020: My plant inventory has just been published. AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MULEGÉ, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO.

I’ve mentioned several times in previous posts that I’m working on a plant inventory (or checklist) for the Mulegé region. But what does that really mean?

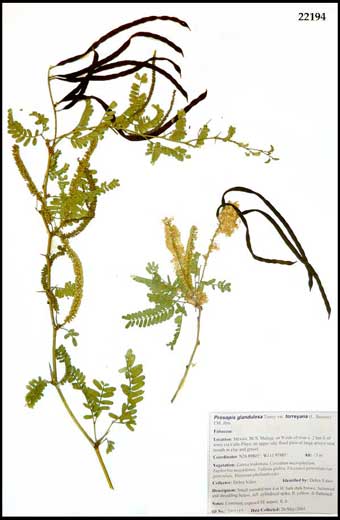

Putting together a checklist is more than just making a list of the plants observed and/or photographed. To be of real scientific value, a checklist should reference specimens that have been collected in the area under study and then deposited in an herbarium where they are curated.

The existence of a physical specimen not only provides concrete evidence that a particular species occurs in the given area, but it also serves as a hands-on resource for future researchers. Once it is housed in the herbarium, basically a library collection of dried plant samples, the specimen becomes accessible to others to study. The photo on the right shows a cabinet at the herbarium of the San Diego Natural History Museum. Cabinets are arranged by family, genus and species. Most of the manila folders will contain vouchers from either the same genus or species, depending on the number of vouchers of each.

At some future time, a researcher might review the specimen to verify its identification, annotating it if the determination is incorrect or if new information indicates that the specimen is actually a previously unrecognized species, variety or subspecies. The specimen can also help researchers studying a specific species, genus or family, because it can provide biological material for morphological, chemical or even genetic analysis.

Furthermore, specimens and the inventories they may be a part of, are a snapshot of what vegetation was present at a given time in a given place. This type of information can help ecologists to understand changes in local or regional vegetation patterns and distributions over time.

Steps in Making an Annotated Checklist

- Define area to be included in checklist

- Collect and prepare vouchers

- Record data for each voucher

- Deposit the voucher with an accredited herbarium

- Search for additional collections by others within the area (herbarium and on-line databases)

- Verify suspect determinations (identifications) of other collections

- Research

- Each species most current name, author(s), and accepted synonym(s)

- Each species APG classification

- Species information, such as life form, distribution and endemism, common local name, local uses...

- Data analysis (e.g., count the number of orders, families, genera, species, infraspecies; give count by life form, number of endemics, rare or endangered species and exotics)

- Get to know the study area, through published scientific or historical information (e.g. vegetational, climatic and geological patterns) and your field observations

- Write article for scientific journal and submit for possible publication

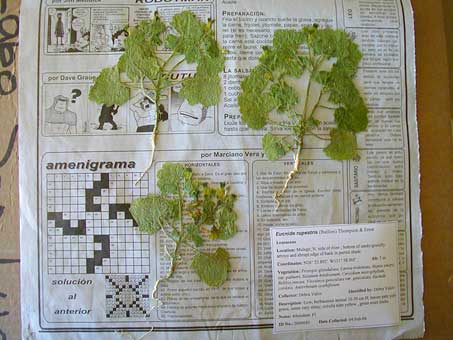

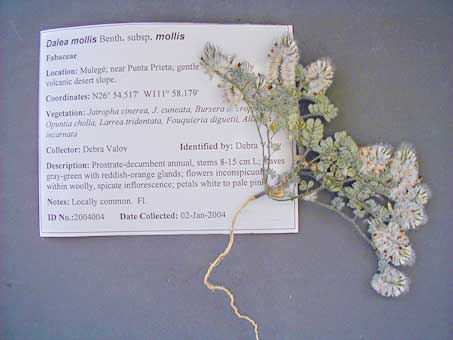

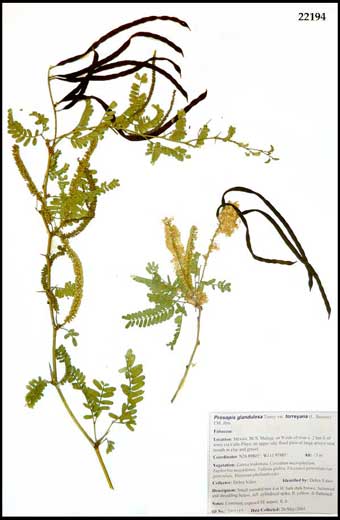

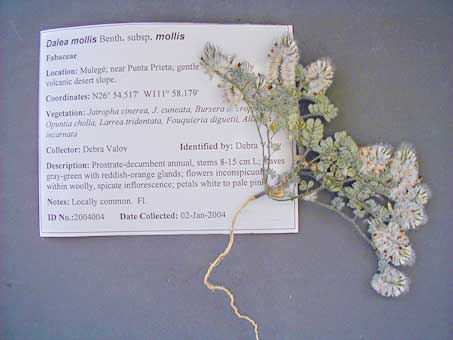

Herbarium specimens are referred to as vouchers. They are pressed, dried samples of a plant that ideally shows common characteristics, and usually includes plant parts, such as leaves, flowers and/or fruit, diagnostically important for their identification. The photo on the right shows one of my vouchers deposited at the herbarium at CIB in La Paz. The plant and label are attached to the sheet with special acid-free white glue and then also anchored over the thick parts with either tape straps, or thread stitches.

Herbarium specimens are referred to as vouchers. They are pressed, dried samples of a plant that ideally shows common characteristics, and usually includes plant parts, such as leaves, flowers and/or fruit, diagnostically important for their identification. The photo on the right shows one of my vouchers deposited at the herbarium at CIB in La Paz. The plant and label are attached to the sheet with special acid-free white glue and then also anchored over the thick parts with either tape straps, or thread stitches.

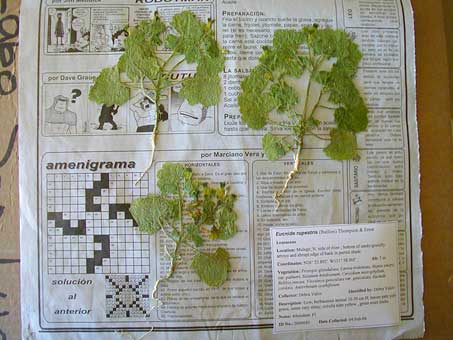

I use an ultra light-weight field press that I made from a piece of medium-weight canvas, nylon straps with adjustable snap-in connectors and about 10 sheets of cardboard cut to fit (each about 14 x 18 inches). Between cardboards, a folded sheet of newspaper is placed with the plant spread out to show its various features. I use one or more pieces of felt, cut to the size of the press, to help fill in the spaces around the plant parts to assure that everything gets nicely flattened right from the start.

When I return home, I move the specimens into my regular, home-made press, which is made of two sheets of plywood and adjustable straps. After rearranging the material, flattening and trimming as needed, and adding padding as needed, the straps are tightened, a job that usually requires me to stand or kneel on the press while I cinch it down.

To aid drying, I place the press outside in the sun in a windy place for a number of days. Even though the humidity here is generally very low, drying can be a problem when it's cold or it becomes muggy. Plants mustn’t be allowed to mold, or the specimen will be ruined, and I've lost a number of specimens that way. I used to use a simple cardboard solar oven to help with drying but now that we live where we have AC power, I have gone upscale with a wooden box (it appeared on our patio one year after a flood and holds the press perfectly) and a low-wattage light bulb for consistent heat 24/7 as needed. For very juicy plants, I check the specimens every day and change damp paper, felt or cardboard as needed.

High-tech field vehicle and equipment

High-tech field vehicle and equipment

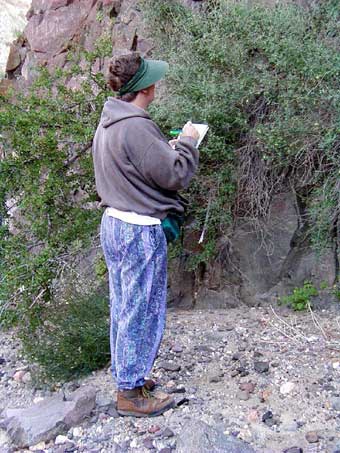

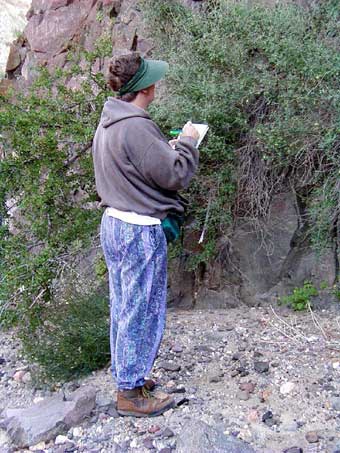

Taking field notes for the day's collection

Taking field notes for the day's collection

Field press (left) and regular presses (right).

The herbarium sheet measures 12 x 16 inches, so when taking a specimen, it is important to keep those maximum dimensions in mind as well as the space on the sheet that will be taken up by a label and other markings, such as the herbarium’s stamp and barcode label. Long plants can be bent and folded (in half or zig-zagged several times) to allow for the display of an entire plant, such as a grass, from root to the tip of the inflorescence.

Herbs small enough to fit on the sheet are usually dug up whole. For larger perennials, shrubs and trees, only a representative piece is collected. Generally, for each species, 3-5 duplicate vouchers are made from the same plant or population.

Dried specimen of an annual herb, complete with roots.

When cut to fit easily in a folded newspaper page, a specimen like this branch of a shrub with flowers and buds will easily fit on the herbarium sheet. I prefer the smaller sizes of the free newspapers.

Along with the plant sample, specific data on each specimen needs to be recorded. I write this information in a collection notebook and then transfer it to my database, from which I can track and analyze my collections and most importantly, easily generate the labels that accompany the vouchers to the herbarium and are attached to the voucher sheet. In the field, I record:

- Date

- Collection #

- Location

- Coordinates and altitude (from GPS)

- Habitat

- Soil type and topography (e.g., rocky hillside, silty arroyo bed)

- Associated plant species

- Life form (e.g., annual or perennial herb, shrub, tree, vine, cactus)

- Dimensions of whole plant and/or parts.

- Habit (e.g., prostrate, erect)

- Color (e.g., petals red, fruit black)

- Fragrance/smell (e.g., skunky, sweet, fetid, no odor)

- Note on abundance/dominance and phenological state.

Back at the house, I do my best to identify any unknown plants. I will key them out using The Flora of Baja California by Ira Wiggins (1980), the “current bible” of Baja plants. Wiggins has over 2900 species, but currently over 4000 species are recognized on the peninsula, so there’s a huge gap involved when trying to ID something I’ve not seen before. The Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Baja California, Mexico by Rebman, Gibson and Rich (2016) is now available to download for free here as a PDF. The associated Bajaflora.org website is now accessible to the public and has many powerful tools, among them the fully imaged synoptic collection for the peninsula as well as their voucher collection database.

I also refer to the Jepson Manual (1983 and/or 2012) and the manual's online efloras. CalFlora is another helpful source for images and links to the Jepson Manual treatments. Another important internet site, which I use to help narrow down or rule out possible IDs is SEINet, which is available to the public and has image galleries of both live plants and voucher sheets for Sonoran Desert plants. It lacks many of the peninsular endemics, but those species that occur on both sides of the Gulf are usually available and georeferenced collection data is also available, showing species distributions in the US and Mexico.

Finally, the current volumes of The Flora of North America (north of Mexico), available at efloras, is another excellent resource and their keys and descriptions have been extremely helpful, especially when dealing with new weed species or species that do occur south of the border.

If all else fails and I can’t identify the plant with any certainty, whether to family, genus or species level, I will contact Jon at the SDNHM herbarium or leave the name blank on the label and let the expert take the 30 seconds or less needed to correctly identify it (I kid you not…Jon has gone through a pile of specimens I couldn’t find in any references and had spent hours trying to nail down, and in less than 5 minutes had identified them at a glance or compared them with the synoptic collection, at which time he showed me the key characteristics. Talk about feeling like a dunderhead sometimes!)

Once I have successfully (I think) identified a plant, I will then check the above sources for the current name and author citation that is part of the determination, as well as check on The Plant List website.

Sample entries in checklist

* Holographis virgata (Harv. ex Benth. & Hook.) T.F. Daniel subsp. glandulifera (Leonard & C.V. Morton) T.F. Daniel [Berginia virgata var. glandulifera Leonard & Morton]. Sh. Leon de la Luz 3657; Valov 2004018, 2004080. [SCB-WC, SCB-AF]

▲ Cryptostegia grandiflora Roxb. ex R.Br. Vi. I. W. Knobloch 2350. Cuerno, Chicote.

Key: * = endemic to peninsula; ▲ = exotic weed; SCB-WC = scrub of dry water course; SCB-AF = scrub of alluvial fan; Vi. = vine; Sh. = shrub.

Note: Plant names within brackets [ ] are synonyms of the currently accepted name. A surname and number combination (e.g. Knobloch 2350) represents Knobloch's voucher with the collection number 2350.

So, that's basically the fun part of making a plant inventory. The research part (mostly steps 7a-d above) isn't as much fun and is rather tedious and time-consuming for a number of reasons, the major one being that botanists keep changing plant names and even moving species and genera into different or new families. The only thing to do is stay on top of the changes as best as possible and publish the list before some major upheaval occurs in the world of botanical taxonomy.

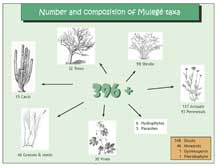

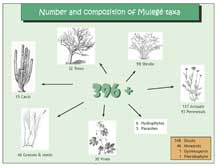

Here's an educational flyer I made for our local Expo, showing the preliminary statistics from my list (click for larger image):

So, that’s it for this month´s entry. Who knows what I´ll get up to between now and next month! ¡Hasta pronto! See you soon!

— Debra Valov, curatorial volunteer

High-tech field vehicle and equipment

High-tech field vehicle and equipment

Taking field notes for the day's collection

Taking field notes for the day's collection