This section contains entries about our botanizing in Baja California written for the UC BEE (Oct 2012 to Aug 2021)

and The UC Hive (2022-), monthly newsletters for volunteers and staff of the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden.

Click on any photo for a larger image.

BEE APRIL 2018

The Comondús

This month, I want to share some of the photos from our trip to several small towns located on the western drainage of the Sierra la Giganta as well as on the Pacific Coast. While our main destination is located only 100 km (60 miles) almost due south from Mulegé as the crow flies, the shortest route it is about 150 km (93 miles) and 5-8 hours via highway and then poorly maintained dirt road. We opted for the longer route: about 380 km (240 miles) and 4.5 hours south, west and then north in a big loop via highway. This latter route first took us south along the Gulf side of the Sierra la Giganta, then west over the sierras to the agricultural town of Ciudad Insurgentes on the Pacific side (located in what is known as the Magdalena Plain ecoregion). We turned north there onto Hwy 53 (in parts divided and well maintained and, in others, shoulderless and lacking a center line) from which we then took paved side roads to reach each of our three main destinations: the Comondús, La Purísima and San Juanico.

There was so much to see and do but because of limited time, this was just going to be a short, exploratory trip during which we hoped to find out if we wanted to come back and spend more time

in the future. There was such diversity on the trip that this month I´m only going to cover our time getting to and then around our first destination, the isolated oasis pueblos of San Miguel de Comondú and San José de Comondú.

There was so much to see and do but because of limited time, this was just going to be a short, exploratory trip during which we hoped to find out if we wanted to come back and spend more time

in the future. There was such diversity on the trip that this month I´m only going to cover our time getting to and then around our first destination, the isolated oasis pueblos of San Miguel de Comondú and San José de Comondú.

Mulegé to Los Comondús — February 10-11, 2018

View of the east flank of the Sierra La Giganta just south of Bahía Concepción andthe junction with the graded portion of Hwy 53 to San San Isidro, gateway to both the Comondús and La Purísima from the east. Deep alluvial volcanic soils in foreground & mountain volcanics behind.

The desert flora of the Magdalena Plain Ecoregion bears some resemblance to that of the Gulf Coast region, but one big difference is that many plants derive most of their moisture from coastal fog. One such species is seen here in Cuidad Insurgentes, where the epiphytic Ball Moss/Gallito (not a moss but the bromeliad Tillandsia recurvata) adorns powerlines and other plants and structures.

One of the disjunct populations of Espadín (Euphorbia ceroderma) is found on the Pacific coast west of the Sierra La Giganta from at least around the turnoff to the Comondús north to near San Juanico. The geology here is made up of ancient sea beds, similar to the soils at Punta Chivato. See image of the plant and flowers here.

One of the exciting events for our traveling companion was stopping to see for her first time a population of Creeping Devil Cactus (Stenocereus eruca), a BCS endemic with a small and rapidly shrinking range along parts of the Pacific Coast.

The usually single-stemmed cactus grows slowly along the ground, the distal end rooting as it grows & the basal part eventually dying off.

We'll be making a right turn up ahead at about Km 60 north of Cuidad Insurgentes. Until here we've been driving through large swaths of agricultural fields eating into the native coastal desert scrub.

After inviting us to stop by his house anytime for un cafecito, off he drove, with us close behind, heading northeast towards the Comondús about 40 km away.

First water crossing as we enter the canyon.

Columnar basalt outcrops are scattered along the canyon from the east end to at least San Jose de Comondú.

The road winds up the canyon, gradually gaining altitude. The debris fields between the canyon walls and the bottom were full of huge, heavily-branched Organpipe Cactus (Stenocereus thurberi) which in places overwhelmed the tree-like Cardón (Pachycereus pringlei).

Rubbervine coiling back on itself. All the shrubs & trees, including the native Huitatave (Vallesia sp., Apocynaceae), Huisache (Vachellia farnesiana v. farnesiana, Fabaceae) & Mezquite (Prosopis articulata, Fabaceae) were being colonized.

At Km 34 we approach a small grade that will take us into the town of San Miguel de Comondú.

Coming into town on the main street, one of just two. The road continues into the distance & the small town of San José de Comondú about 4 km (2 mi.) away.

Happy to be out of the car I was soon wandering around in the bushes instead, and quickly came across a new-to-me species: Crested Anoda/Violeta del Campo (Anoda acerifolia, Malvaceae).

In the orchards of the oasis. Native Washingtonia fan palms and introduced citrus (oranges, limes, grapefruit, mandarines), mangos, olives, grapes, and date palms (tiny tree in foreground) are mixed in here. The Jesuit missionaries brought many of these species with them in the 18th Century.

Sugarcane is another major crop in this and the La Purísima arroyo. Cane is ground in traditional presses powered by mules. The juice is cooked down in large copper pots on wood fires and the syrup is poured into wooden molds that have belong to families for generations. The resulting piloncillo, a conical block of hard, unrefined sugar, is sold in stores across the region. We especially favor the almost black ones, rich in molasses and flavor.

Neatly stacked and stored leaves of the Washingonia robusta palm. Dried leaves are used to make roofs and walls. The teeth-like spines along the edges of the petioles are removed at harvesting.

A well-fed local pig. Products consumed, sold or traded by the owner would include manteca (lard), chicharrones (deep-fried pork rinds), carnitas (tender meat cuts cooked in the big pot used to render the lard), various cuts of meat, and stew bones.

View of Mesa la Yegua on the western flank of the Sierra La Giganta at the opening of Arroyo Comondú which leads up into the Comondús. The soils of this region are primarily of Pliocene-Pleistocene limestone [1] with occasional volcanic overlays.

The dense hairs on the leaves of Tillandsia recurvata soak up moisture and trap nutrients from the air. The area is also host to a wide variety of lichens which can be surprisingly spongy and damp to the touch even on a warm day. The red flowers seen here belong to the Palo Adán (Fouquieria diguetii, Fouquieriaceae) on which the Ball moss and many species of lichen are squatting.

The default appearance of the vegetation on the Pacific coast: lots of grayish, leafless shrubs (Palo Adán, Fouquieria diguetii; Ashy limberbush, Jatropha cinerea; Little-leaf Elephant Tree, Bursera microphylla); green Creosotebush (Larrea tridentata); columnar cacti like Cardón (Pachycereus pringlei) and Pitahaya agria (Stenocereus gummosus); and lots of it covered with grayish-green Tillandsias and lichens. With the occasional flower.

I don't exactly know why I find them to be so whimsical. They make me think of a bunch of lolling sea lions on the beach, a few poking theirs head up to see what all the ruckus is about.

The spines are dense, sturdy & sharp. Ever see images of a lamprey mouth and all those teeth? The Creeping Devil could be related!

But first, time for a chat with the friendly tractor driver who stopped next to us where I was taking a photo at the juncion. As seems to be the case here, it didn't take us more than a minute or two to introduce ourselves and figure out who we knew in common. In this case, we've known his brother in Mulege for years.

For quite awhile we seemed to parallel the mountains but with the first curve after many kilometers of arrow straight road, we finally began to approach them. First good view of the canyon mouth.

Not a lot of variety in the hydrophytic vegetation. Small native fan palms (Washingtonia robusta), the exotic & invasive rubbervine (Cryptostegia grandiflora, Apocynaceae) and Bermuda Grass (Cynodon dactylon, Poaceae) were the top plants at this site.

Tributary branching off the main canyon. Lots of water and dense riparian forests of leguminous trees (Mesquite, Palo verdes).

Another water crossing. The Rubbervine was well-established here. Now I can clearly see why it is considered a noxious, invasive species.

The fruit of Rubbervine. The two follicles are each about 15 cm long and have many small seeds with comose tails. Other species along the edge include Bacopa monnieri (Plantaginaceae), Buena mujer (Chloracantha spinosa, Asteraceae), Bermuda Grass.

View back from on top of the grade to the lush arroyo bottom.

The town had a facelift a few years ago when the roads were paved, sidewalks added & street lights erected, the cobblestones & paving stones harking back to the mid 1800s.

This Anoda was sprawling & acting a bit vine-like. The triangular leaves had a red tinge along the mid vein. The flowers are about 15 mm L x 20 mm D. It was in the shade in the palm orchard.

An acequia (irrigation ditch) in the palm orchards. These are likely remnants of the original ditches in use for generations. Some date back to missionary times. Most of the oasis towns in Baja have at least remnants of these original irrigation systems.

One of the local gardens. The gate is made with large-screen wire mesh and the cleaned, central ribs of date palm leaves are woven into it. Cardon ribs are also used in fencing, gates, doors and the underlying structure for palm roofs.

Fan palm leaves spread out to dry. Well-maintained orchards are regularly pruned. Neglected trees will form a long, dense skirt of leaves that poses a huge fire hazard. In Mulegé, the leaves are currently priced at 3 pesos (16 cents) each.

Local turkey strutting his stuff. They are eaten during winter holidays.

San José de Comondú — February 11, 2018

The road to San José de Comondú. The volcanic escarpment on the right, with its columnar formations, & the "river" and oasis on the left. Agricultural fields are located within the oasis all along the river.

In the distance at center top, the left (northern) wall of the canyon with its columnar formations becomes visible.

This road connects back to Hwy 1 on the Gulf side via San Isidro. We considered taking it from here to La Purísima but were discouraged by the locals who said it really was in terrible shape and a 3 hour trip.

Downtown and another wonderful façade. Nothing back there but an empty lot and a few weedy palo verdes!

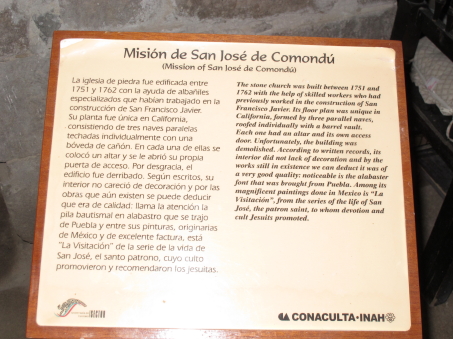

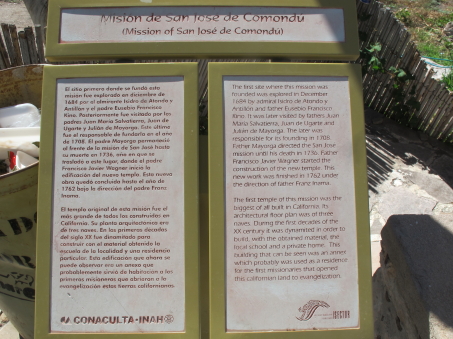

Mission San José de Comondú. According to one of the locals we met, the mission was originally founded in the town of San Miguel, but moved upstream in the early years when they realized that there wasn't enough water to sustain the settlement.

Mission San José de Comondú. According to one of the locals we met, the mission was originally founded in the town of San Miguel, but moved upstream in the early years when they realized that there wasn't enough water to sustain the settlement.

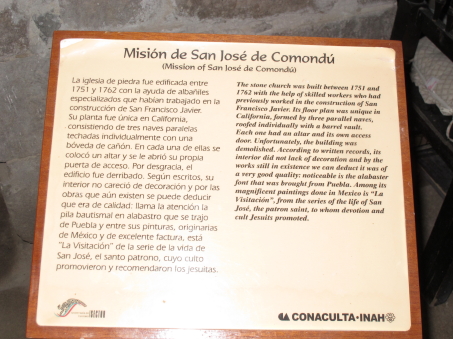

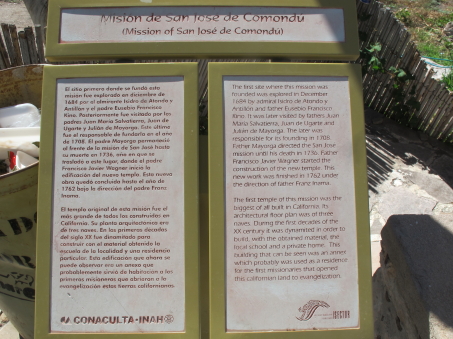

Interpretive sign inside the church.

Subdelegación San José de Comondú or the local City Hall.

The canyon walls were fascinating, as were the giant Organpipe cacti. Vertical cracks were evident, as were places where water had obviously eroded the sharp edges of the columnar structures.

La Biblioteca Pública or Public Library looks likes it's taken a beating over the years, and wasn´t open midweek.

Getting close to downtown!

View of the mission grounds. The fence is made of date palm ribs wired together. That's a date palm on the left, and a coconut palm to its right behind the fence.

Inside the present Mission. In places, the walls which are made of a type of local volcanic rock called "cantera", are easily 4 ft thick.

There are lots of rocks here in the Sierra and they are put to good use as retaining walls, fences, corrals and planters.

You can find more images of the interesting, historical buildings and structures of the Comondús on this page.

That's it for now. In the June entry (in two months), I´ll continue with the rest of this trip, including the oasis village of La Purísima and the beach town of San Juanico. Until then, hasta la próxima…

Debra Valov—Curatorial Volunteer

References

[1] Minch, J., Minch E. & Minch J. (1998). Roadside Geology and Biology of Baja California. p. 114