THE UC HIVE MARCH 2024

Vines: Description and Adaptations for Desert Life

The rains this past summer have been very good to our local vine species. Being a vine has certain advantages over other species in this arid environment that contribute to their success. So, given the numerous species that I’ve come across, I’ve decided to dedicate the month’s entry to this highly adaptable growth form.

What is a Vine?

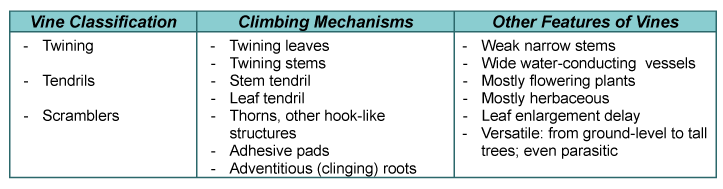

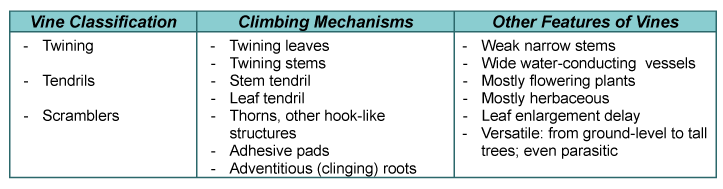

A vine is basically any plant that has a trailing or climbing (scandent) habit with a growth form based on long stems. The stems of vines generally lack the internal support structures necessary for upright growth, but they usually have increased tensile strength that allows them great flexibility and resistance to pulling and breaking.

Desert Starvine (Brandegea bigelovii) creates massive bowers in the Mulegé Valley. There are several shrubs & Elephant Cactus under all that.

Manto de la Virgen (Jacquemontia eastwoodiana), a perennial vine endemic to BCS, covers several shrubs and climbs up into the lower branches of a tree.

Vines can be herbaceous or woody (the latter often called lianas, especially those in the tropics). Some species always grow as vines while others will climb where there is a supportive structure available or grow at or near ground level where there is not. There are also parasitic vines that attach themselves within the plant's tissue and then send out haustoria (threadlike stems) that find new points of attachment on the host plant in order to grow larger and increase the amount of nutrients it can steal.

Desert Starvine growing across the ground and annual grasses.

Old Desert Starvine covering Cholla and Galloping Cactus stems.

Slimjim Bean (Phaseolus filiformis) is an annual, twining vine. It can reach many meters long, growing across the ground or up into large plants.

Butterfly Vine (Callaeum macropterum) is a woody twining vine that can have stems 5+ meters long and like here, 2+ cm D. Without support, it will sprawl.

A parasitic Dodder (Cuscuta legitima) sends out long orange stems (haustoria that lack chlorophyll) across an annual Sandmat.

Another Dodder (Cuscuta tuberculata) wraps its thready penetrating haustoria around a stem & flower head of Bajacalia crassifolia.

Vines are also divided into categories: those that are twining and twist themselves around other plants and objects; those with tendrils or other modified parts for attachment to aid in climbing; and those that are scramblers, growing mostly across the ground or up and over other plants without twining or attaching themselves.

Passiflora pentaschista (left) uses tendrils while Phaseolus filiformis (right, with pink flower) is a twiner.

Jacquemontia eastwoodiana, una enredadera con la base algo leñosa, que se ve entrelazada alrededor de varias ramas de otro arbusto leñoso.

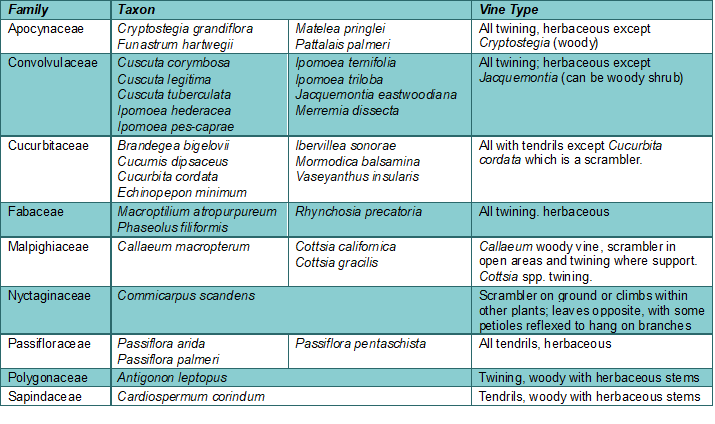

Table 1. Vines: Classification, Climbing Mechanisms and Other Features

Tendrils arise along the stem or from the axil (a modified leaf) as long, wiry extensions that reach out, searching until they come in contact with something to which they can cling. Once it makes contact, a tendril starts to wrap around and coil up until it looks more like a spring. Some species have tendrils that are coiled before even making contact with a target. The plant can tighten or loosen the tendril’s tension as needed for support as it grows.

Leaf tendril of Desert Starvine showing its spring-like coil.

Leaf tendrils of Gulf Vaseyanthus (Vaseyanthus insularis) creating cross-connections that help strengthen the plant's structure.

Leaf tendrils of Baja California Passionflower (Passiflora pentaschista) reaching out to make a connection.

Passionflower leaf tendril looped around a Graythorn branch, anchoring the vine to the shrub.

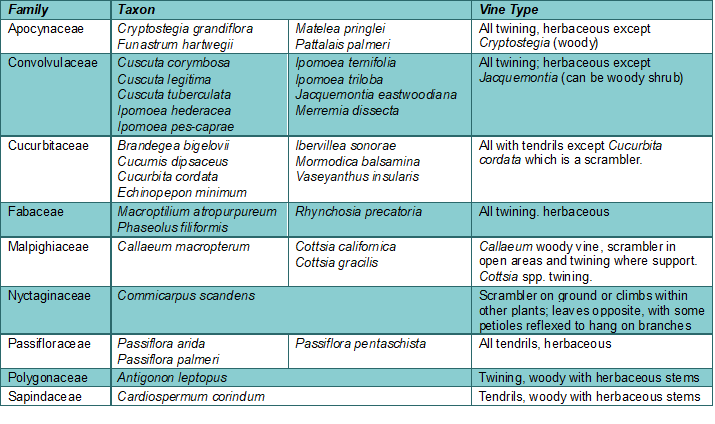

The vine growth form has evolved independently across a variety of plant families. In my area (Mulegé), nine families and at least 33 taxa are represented (see Table 2). These include both woody and herbaceous vines, those that twine and scramble and those with tendrils. We even have parasitic vines.

Table 2. Vines in the Mulegé Flora

Advantages of Being a Vine

Vines are commonly fast growing. Using rocks, plants and other objects for support allows the plant to minimize the resources invested in creating the internal structures necessary for strong, self-supporting stems and putting that energy into maximizing growth to reach sunlight as quickly as possible (image right of long stems of Coyote Melon).

Vines are commonly fast growing. Using rocks, plants and other objects for support allows the plant to minimize the resources invested in creating the internal structures necessary for strong, self-supporting stems and putting that energy into maximizing growth to reach sunlight as quickly as possible (image right of long stems of Coyote Melon).

Being fast-growing, vines can out-compete other plants for sunlight or habitat, quickly colonizing large, open areas. They can also thrive in areas where there is limited fertile soil by rooting where soil is available but reaching beyond the area for sunlight.

Vines can create their own shade or take advantage of shade created by other plants by growing up within them. Removing a great deal of its biomass up off the ground into the higher reaches of other plants (photo at right) can reduce a plant’s exposure to herbivory.

Vines can create their own shade or take advantage of shade created by other plants by growing up within them. Removing a great deal of its biomass up off the ground into the higher reaches of other plants (photo at right) can reduce a plant’s exposure to herbivory.

Getting off of the desert floor also means that the plant can reduce exposure to the high temperatures on the desert floor (can easily be 10-20° F cooler at 1.25 m above the surface).

Being higher up can also mean increased air circulation that can reduce the plant's temperature as well. This can be categorized under growth adaptations of desert plants.

When looking for information about vines on the internet, I was surprised that I could find no open-access resources specifically about vines in desert environments; in contrast, information about tropical and subtropical vines was abundant. There are also plenty of resources about the adaptations of plants in general in arid regions and most of these apply to vines as well because as one source [1] wrote, "Vine species in arid and semi-arid areas of the world occur in a remarkably broad range of growth forms although none of these is unique to such areas [emphasis mine]."

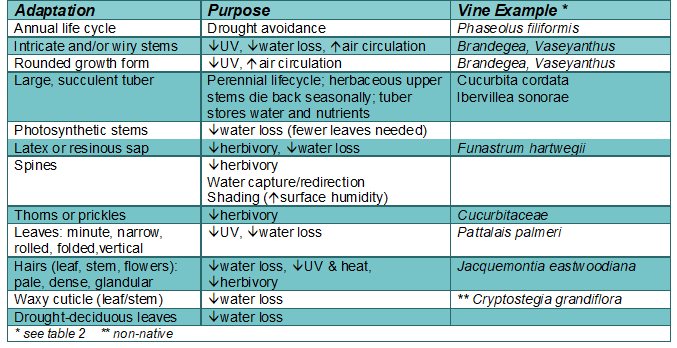

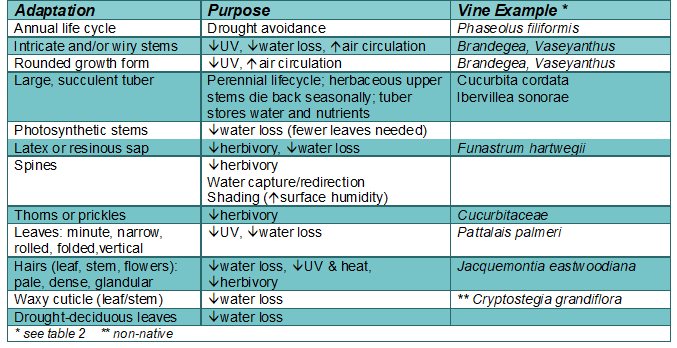

Table 3 below lists adaptations that are not necessarily unique to vines, but which many desert vines possess by virtue of being a desert dweller that needs to conserve water, reduce UV exposure, deal with high tissue temperatures and desiccating winds and a variety of 4 and 6-legged herbivores. The examples provided are from the Mulegé Flora (Valov 2020) and it should be noted that the mentioned taxa may have more than one adaptation.

Table 3. Common Desert Plant Adaptations and Sample Vine Taxa

The succulent tuber of Baja California Coyote Melon (Cucurbita cordata). This 15 cm long tuber was c. 1 m below ground but was exposed when the bank was washed away. The herbaceous perennial dies back to below ground after its fruit mature to conserve water.

The tuber of this species of Coyote Melon (Ibervillea sonorae) is tough yet succulent. Its looks like a rock & can store water & nutrients to support the plant for several years [2]. It is a woody vine with herbaceous upper parts that die back by summer to conserve water.

Hairy leaves & twigs of Balloon Vine (Cardiospermum corindum). In many species, like this one, pubescence may vary from little to dense depending on weather, water availability and habitats.

Closeup of the leaf surface of Jacquemontia eastwoodiana which is velvety to the touch. The hairs act like clothing, reflecting UV & also keeping the surface of the leaf humid, which decreases water loss.

Hairs on the stems & leaves of the BCS endemic Baja California Passion Flower help conserve water. Along with the tacky, stinky (dissected) flower bracts, they also discourage herbivory.

Milkweeds in the Dogbane family like this Climbing Milkweed (Funastrum hartwegii) have a milky, latex sap that is both toxic & gums up insect mouthparts. Our two local species have narrow, lanceolate leaves.

Coral Vine (Antigonon leptopus) is a deciduous, perennial woody vine with herbaceous stems that climb quickly into other plants & can cover large areas on the ground. It is native to Mexico; elsewhere in the tropics & subtropics it is considered an invasive weed.

The large, rugose leaves of Coral Vine are arrow or heart-shaped. Flowers arise from axillary racemes or terminal panicles with

two terminal tendrils and have five showy tepals each 4-10 mm L & 2-6 mm W which become papery with age & loosely enclose the achene.

The 1.5 m H x 2.5 m D mound here is actually a large Sweetbush (and maybe other unknown plants) mixed with, and covered by, Butterfly Vine stems. The stems in the foreground are exploring new territory.

The Butterfly Vine has completely engulfed most of the Sweetbush and whatever else is beneath it. Only the occasional flower heads indicated what was beneath.

Butterfly Vine bush stems twining on themselves.

Flowers and fruit of Butterfly Vine bush.

Balloon-vine/Tronadora (Cardiospermum corindum). This is a woody perennial with herbaceous stems. Compound leaves are 3-lobed.

Young 3-angled, 3-chambered inflated capsules. The sepals are still visible above the fruit. Mature fruit are c. 4.5 cm L x 3.5 cm D.

The flowers of Balloon-vine have 4-5 sepals, the outer two smaller than the inner 2-3 (c. 2-5mm L), 4 white petals and 8 stamens.

The papery fruit resemble small Chinese lanterns hanging from the branches. A common name in Spanish is farolitos, little lanterns.

Eastwood Clustervine / Manto de la Virgen (Jacquemontia eastwoodiana) can grow as a low, woody shrub with some upper vinelike branches, or as more of a wide-reaching, twining vine.

Eastwood Clustervine is a BCS endemic, ranging from near Santa Rosalía southward to La Paz & on several adjacent Gulf islands. It can be seen after summer rains blanketing plants from fall to early spring.

The stems of Eastwood Clustervine starting to overtake a baby Palo Verde tree.

The flowers of Eastwood Clustervine are blue-violet, 2-2.5 cm D and broadly campanulate with a short tube and 5 short white stamens.

Coyote Melon (Ibervillea sonorae) is a vine that grows from a large tuber. The ripe fruit are bright orange & the fleshy interior deep red. Unlike our other very bitter Coyote Melon, the fruit is sweet.

The flowers of Coyote Melon are dioecious, the pistillate flower solitary in the axils & the staminate on short racemes. The leaves are deeply lobed 5-7 times & c. 5-9 cm L x 5 cm W.

Side view of another Coyote Melon tuber. Several woody stems can be seen on the top of the tuber, growing up, crossing and changing direction, with most growing to the left.

Gulf Vaseyanthus is monoecious with single axillary pistillate flowers & staminate flowers in short racemes. The pepos may be prickly, or smooth like here. Each is only about 1 cm D with a 5 mm L beak.

Baja California Coyote Melon/Calabacilla amarga (Cucurbita cordata). The stems reaching toward the camera were over 4 m from the center of the plant.

Baja California Coyote Melon. The flowers are monoecious: staminate in fore- and background. Pistillate with ovaries (fruit, center).

The attractive foliage (leaves are cordate in outline but deeply cleft) & baseball-sized bitter fruit of Baja California Coyote Melon.

2010 saw a bumper crop of Baja California Coyote Melon. This scene was repeated over and over throughout the Mulegé valley.

Flowers of the parasitic Reflexed Flat-globe Dodder / Chupones / Fideos (Cuscuta legitima).

Flowers of another parasitic vine, Tubercle Dodder / Fideos / Chupones (Cuscuta tuberculata).

A third local parasitic species, Large-flower Dodder (Cuscuta corymbosa). It is more sizeable than the first two & its bright orange stems are quite showy when blanketing grasses or other shrubs.

Climbing Milkvine (Funastrum hartwegii) is an attractive plant with its cymes of showy flowers. Flowers are 4-8 mm D with furry purple or pink & white lobes.

The ubiquitous Slimjim bean (Phaseolus filiformis), a slender native annual vine that is common and widespread. I just love the tiny lime green, corkscrewed keel petals at the center of the flower.

The prolific Sonoran Passion Flower (Passiflora pentaschista) is a BCS endemic & has done well this season, occuring in arroyos & bajadas across the area. Flowers are 2.5-3.5 cm D with 5 white petals.

Wow, that's a lot of vines for our small area. Amazingly, of the 11 taxa pictured here, all but two (Cardiospermum and Funastrum) have been in bloom or fruiting since we arrived in October. An additional four that were in bloom are not included here.

For a full list of this month's plants and animals (with family, latín name and common names in both English and Spanish), visit this page.

That´s this month´s entry. Life is like a vine, you never know which way it will grow, and since there's still plenty of plants to investigate and share, watch out for next month's entry. Until then, hasta pronto...!

Debra Valov — Curatorial Volunteer

P.S. Forgive me, I couldn't resist these viney puns [3]:

What's the worst mistake the vine ever made? It went out on a limb—and fell flat!

Why did the vine go to therapy? It wanted to untangle its problems.

How does a vine apologize when it makes a mistake? It leafs an apology.

References and Literature Cited

iNaturalist. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. (Accessed January 2024)

[2] Knox, Alice Adelaide (July 1907). "The stem of Ibervillea Sonorae". Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 34 (7): 329–344. doi:10.2307/2478988. JSTOR 2478988 [accessed 07-Feb-2024].

[3]Punsteria. Discover Over 200 Hilariously Witty Vine Puns In One Place. Accessed 7-Feb-2024 at: https://punsteria.com/vine-puns/

Rebman, J. P., J. Gibson, and K. Rich, 2016. Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California, Mexico. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History, No. 45, 15 November 2016. San Diego Natural History Museum, San Diego, CA. Full text available online.

Rebman, J. P and Roberts, N. C. (2012). Baja California Plant Field Guide. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. Descriptions and distribution.

[1] Rundel PW, Franklin T. Vines in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. In: Putz FE, Mooney HA, eds. The Biology of Vines. Cambridge University Press; 1992:337-356. Summary at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511897658.014 [accessed 07-Feb-2024].

Valov, D. (2020). An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Mulegé, Baja California, Mexico. Madroño 67(3), 115-160, (23 December 2020). https://doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-67.3.115

Wiggins, I. L. (1980). The Flora of Baja California. Stanford University Press. Keys and descriptions.