THE UC HIVE APR 2024

Mulegé: Arroyo de Canett

January 2024. It’s just this season that I discovered, or should say, rediscovered a botanical gem of a location. And it turns out it’s located only about 100 meters from where we now live in Mulegé.

January 2024. It’s just this season that I discovered, or should say, rediscovered a botanical gem of a location. And it turns out it’s located only about 100 meters from where we now live in Mulegé.

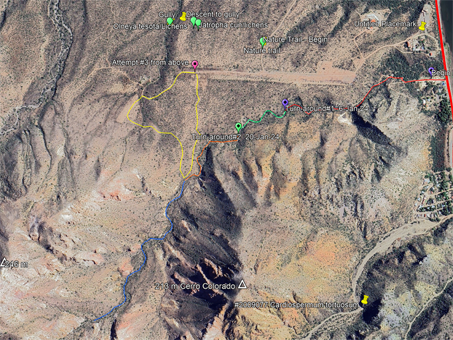

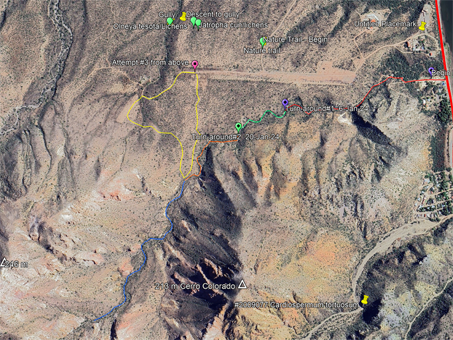

It has been at least 20 years since I walked up the canyon and I have no idea what kept me from exploring it before now. Looking at the Google Earth map and using the path tool it looks like it extends at least two kilometers up into the Sierra Azteca. It’s hard from the map to tell the how much elevation gain there is, what the terrain is really like and how far it continues as an arroyo or if it just turns into a meandering ditch across the bajada. East is at the top of the map at right.

I have walked up the arroyo a number of times since January and have even approached it from the bajada above, looking for a potentially easier way to get down into it and to a starting point farther upstream than I had previously reached via the bed. This same arroyo is where I took many of the photos from last month’s issue on vines.

Looking south down into the arroyo

from the W edge of the bajada.

Looking NW and down from the edge of the bajada into the upper part of the arroyo. More of the Sierra Azteca is visible at right.

The arroyo cuts into the alluvial fan (bajada) at the base of the Sierra Azteca and more specifically around the east and northern base of Cerro Rojo. It creates a more or less steep bank and slope on the west side of the arroyo, with a shallower, more tapered bank on the opposite side.

Looking west towards Cerro Rojo (tallest peak at 213 m) as I cross the alluvial fan (bajada) in the foreground & get closer to the edge.

Looking east, down the bajada from the same point, at the mouth of the river, the Concepcion peninsula & the Gulf of California.

The outwash of the arroyo is to the north and above the river road, and when there is heavy enough rainfall, it flows over the road into the river. The soil of the open, highly disturbed area consists of sand, small gravel and fine volcanic alluvium. Many of the species are fast growing, prolific native annuals like Watson Amaranth (Amaranthus watsonii), Orange Globemallow (Sphaeralcea ambigua var. versicolor) and Desert Horse-Purslane (Trianthema portulacastrum) or non-native annuals and perennial like Castor Bean (Ricinus communis) and Buffel Grass (Cenchrus ciliare).

The open area of the mouth with the desert scrub in the background.

Same area looking a little more to the east and the bank in the distance.

At the uppermost margin of the outwash area, just before the desert scrub begins, I found a number of species that are more commonly found on the rocky slopes or along the bank edges of arroyos, and that were abundant upstream in this arroyo (see Aldama, Hofmeisteria, Jacquemontia, Passiflora below). These perennials all looked fabulous and appeared to be thriving in the full sun and fast draining soil.

Coast Hofmeisteria (Hofmeisteria fasciculata var. fasciculata

Coast Hofmeisteria is a perennial and is thriving here.

Smooth Fagonia (Fagonia laevis) is a delicate, non-glandular but prickly perennial. Fl is c. 1.5 cm D.

The stipules impart Fagonia's prickliness. The fruit, a capsule, has a pointy tip. Plant 30 cm H x 50 D.

As we saw last month, given the chance, vines will be vines, and some of the Passiflora was conquering a clump of Buffel Grass and old Amaranth stems, while a tiny Jacquemontia had found a bare woody stem a few feet high and was busy winding its way up.

Baja California Passionflower (Passiflora pentaschista) was engulfing anything it could climb on or over near the mouth of the arroyo.

Eastwood Clustervine (Jacquemontia eastwoodiana) has found a good purchase on an old stem and is climbing to new heights.

Baja California Passion Flower above and Palmer Passion Flower (Passiflora palmeri) covering a Mesquite tree near the mouth.

Palmer Passion Flower with several bee butts sticking out. Almost every flower on this plant had several bees working at the flower bases.

An extra photo of the bees and flower, just because...

Where the desert scrub and the trail begin.

Moving up the arroyo away from the mouth and looking at it from the level of the arroyo bed, rather than from the level of the bajada above it (see photos above), both banks have a few areas with terraces as well as some sharp cut banks of sedimentary rock and alluvial sedimentary deposits. Outcrops of volcanic tuff (varying sized lava rocks loosely or firmly cemented into large blocks by volcanic ash) are also present. The path is meandering and the soil variable, from loose and gravelly to bouldery, with a number of places where the overhanging spiny or pokey shrubs and trees create a challenging obstacle course.

Looking back towards the mouth from a flat, gravelly section near the beginning of the arroyo, .

Cardón, Cholla and Hedgehog Cactus on one of the rocky outcrops early in the walk.

This wall of rock has some interesting holes in it. I would surmise that they were formed by gas in the volcanic rock and weathered by water.

Tuff breccia, volcanic rocks and boulders cemented by solidified volcanic ash. These types of formations look a lot like someone went crazy with a cement mixer.

Another flat, gravelly section of the arroyo. It soon starts to narrow and the ground gets more rocky.

The path splits for a short distance, following the original bed on the left and a flat, parallel track on the left for quarry access.

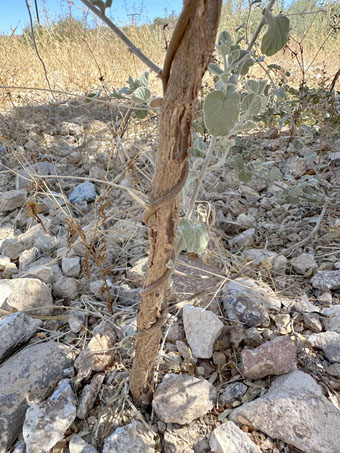

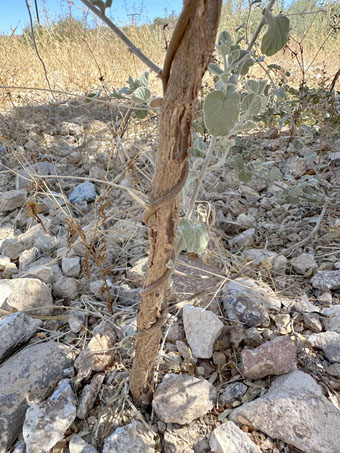

Green Snakewood / Palo Colorado (Colubrina viridis) is possibly the most common and abundant woody plant here, at least along the first kilometer.

The red bark makes it easy to understand why it's called Palo Colorado.

The banks and the terraces slightly elevated above the arroyo bottom are home to more shrubby plants and trees. Palo Colorado, Little-leaf Palo Verde (Parkinsonia microphylla) and Gallineta (Callaeum macropterum) are particularly dominant. On rocky outcrops, cacti like Cardón (Pachycereus pringlei), Cholla (Cylindropuntia alcahes var. alcahes and C. cholla) and Hedgehog Cactus (Echinocereus brandegeei) dominate the more sunny spots while Hofmeisteria and Eucnide spp. thrive in partial or deep shade.

Eastwood Clustervine / Manto de la Virgen (Jacquemontia eastwoodiana) is a tomentose perennial vine with velvety leaves well-adapted to desert life.

Fruit capsules of Eastwood Clustervine sit in cup-like calyces and the dull, rough surface of the ovoid, cocoa-colored seeds may help hide them in the gravelly soil.

Baja California Ruellia / Flor de Campo (Ruellia californica var. californica) is a common & abundant shrub in many habitats, but is especially attractive when it has ample moisture & shade along arroyos. Campanulate flowers are 4.5-5.5 cm L x 2.5-3 cm D.

Click on the image to see the densely glandular herbage that gives Ruellia its tacky surface & distinct, pungent odor. Capsules split open longitudinally to release the seeds.

This is a beautiful outcrop with a very shady base.

A little more of the same high outcrop.

I am always amazed by the number of plants that can be found growing on a rocky cliff with little soil.

The cracked surface probably helps to retain moisture, soil and organic matter.

Cardón, Organpipe (Stenocereus thurberi), Hedgehog (Echinocereus brandegeei) and Cholla cacti (Cylindropuntia alcahes var. alcahes and C. cholla) all occur on this outcrop, along with Coast Hofmeisteria, two Elephant tree species (Bursera hindsiana and B. microphylla), Palo Adán (Fouquieria diguetii), Palo Colorado (Colubrina viridis) and Littleleaf Palo Verde (Parkinsonia microphylla).

Coast Hofmeisteria thrives on shady and semi-shady rock faces and roadcuts. Plants range from just 15-20 cm to well over 1.5 m D, depending on location.

In the deep shade on the same rock outcrop, there were a number of Coast Hofmeisteria hanging down the cliff, creating a 2 m long cascade of leaves.

This Coast Hofmeisteria, growing on the cliff in deep shade, has flat, broad, open leaves that are thin & sparsely hairy.

By comparison, these leaves from a beach cliff dweller are hard to recognize as Hofmeisteria. The succulent leaves are compact and densely pubescent.

Coast Hofmeisteria are also found in the sandy, gravelly soils of exposed arroyo bottoms, likely because so many grow on the cliffs above & the seeds get blown/washed along. This is from the mouth of this arroyo.

This plant, growing in full sun at the arroyo mouth, has more normal-sized leaves with typically reduced leaflets. The succulence is intermediate between shady and beach sites, as is the pubescence.

Cardón form a small forest, or Cardonal on the north side of the high outcrop pictured previously, with a talus slope in the distance.

On the east, a gentle slope rises from the arroyo bottom to the top of the bajada. This may be one of several spots where descent into the arroyo will shorten by half a future upstream excursion.

Advancing up the arroyo.

One of the few non-conglomerate outcrops along the E arroyo bank.

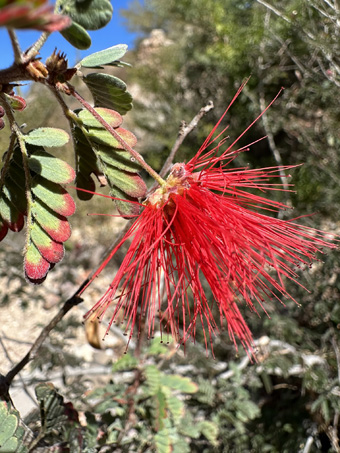

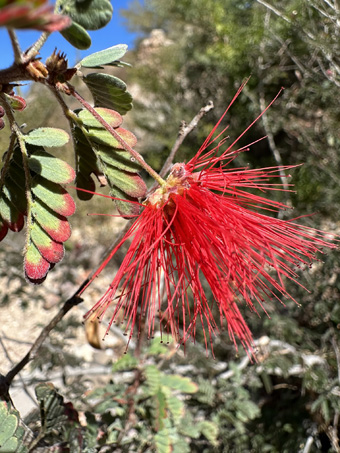

Fairy Duster/Tabardillo (Calliandra californica) is occasional along the arroyos of the Sierra Azteca.

There were new and old fruit as well as new flower buds on several of the Fairy Dusters.

A short detour to the quarry site (created when they built the microwave tower on a nearby peak 10-15 years ago) yielded a few more plant species to add to the list for this arroyo. There seems to be a pocket of what is either old seabed or a thick ash layer – I didn't have time to investigate more thoroughly as I was hot and heading home. It is of course highly disturbed, but plants were slowly moving in to the area. I wasn't surprised to find Desert Trumpet plants, as I predicted that they would likely be present due to the particular soil type they seem to prefer in my area.

Palmer Passion Flower/Granadilla (Passiflora palmeri) is endemic to the peninsula and is a host plant of the Gulf Fritillary Butterfly (Dione vanillae), of which there were many flitting around the quarry.

The herbage is very glandular-pubescent and pungent. The showy white flowers are c. 6-8 cm D, with 5 petalloid sepals and 5 petals abd are attractive to butterflies, bees and even hummingbirds.

Baja California Alvordia (Aldama glomerata var. glomerata) is a near- endemic shrub, from s BC into the Sierra la Giganta in BCS and beyond.

The flower heads are arranged in glomerules c. 2 cm D, each with 3-5 disk & (0)1-3 ray flowers. Involucres & ray florets are 2.5-5 mm L.

Desert Trumpet / Guinagua (Eriogonum inflatum). In northern populations, the stems are usually inflated, but most peninsular individuals do not show this trait & used to recognized as var. deflatum.

The reniform leaves are ephemeral, with a dark green upper and pale, canescent lower surface. While some plants may reach 1 m H with 1 cm D stemsm most indivivuals in this area are ±60 cm with thready stems.

The minute flowers of Desert Trumpet are arranged in small umbels. The 5 tepals of the involucre are 2.2.5 mm L and hairy on the backs.

Scrub farther up the arroyo consists of Palo Blanco, Euphorbia magdalena, Ruellia californica, Desert Ironwood & Little-leaf Palo Verde.

Boulders and spiny shrubs and trees occasionally make the going slow.

A wide spot in the arroyo that soon narrows again at the next curve.

One of several cut banks formed by sedimentary alluvial deposits. The small plants near the base at R are Rock Nettles and Hofmeisteria.

Another of the same type of sedimentary cut banks with more Rock Nettles (Eucnide spp.) and Hofmeisteria.

This (Eucnide rupestris) is the third species of Rock Nettle found in my area. Like the other two species, thrives on cliffs of all kinds as well as arroyo bottoms. And like E. aurea it has very prickly hairs.

Pegapega (Eucnide aurea) is a common annual coastal endemic from around Santa Rosalia to the Sierra la Giganta. I've found that only when the needlelike hairs break off under the skin are they irritating.

Two E. aurea plants, one with greenish-yellow and the other with orange flowers which vary by size & limb shape. I have wondered if there is some promiscuity between E. aurea and E. rupestris.

Flowers of three E. aurea plants, all varying in color & shape. I've seen this same pattern on another similar cliff where I started botanizing long ago at Playa Punta Arena, and where E. rupestris was also present.

Pegapega fruit (Eucnide aurea) elongates as it matures, reaching back to the cliff behind to reseed itself. Pedicels here are c. 12 cm L.

The fruiting pedicels of Eucnide cordata (more common in arroyo beds but found on cliffs), don't elongate to reseed on the cliff.

Another cut bank farther up the arroyo, this one with deep shade. It appears to be a mix of tuffaceous volcanic sediments below with a more mudstone layer above. Any geologists out there to weigh in?

At first this looked like the superficial black coating on some areas of rock were lichens. But it seems that it is likely inorganic in nature because the black extends like a seam throughout the cut bank.

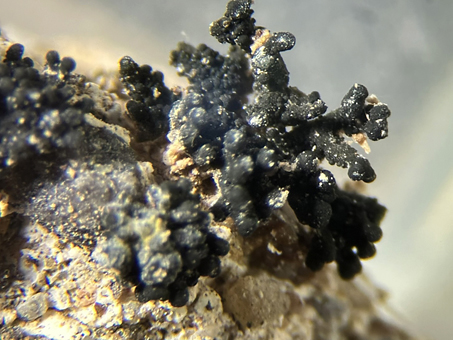

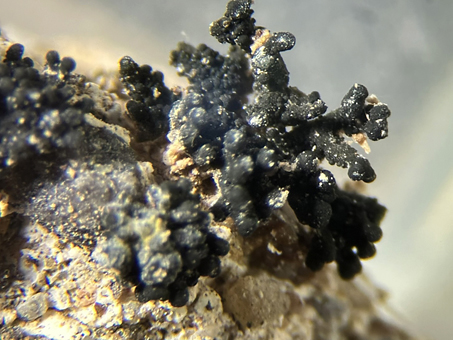

These are tiny, pillowlike lichens growing on various rock outcrops along the arroyo. I uploaded my observations to iNaturalist but the identity has yet to be determined. Compare with a nearby lichen.

Many of the tiniest clusters c. 2 mm in diameter seem to consist of squamulose thalli. Some of the larger clusters (5-12 mm D) start to take on a columnar appearance, with some of the columns branching.

Most of the rock in the outcrops show some degree of cracking. This one is not only colorful in burgundy, orange and black tones…

…but in some parts where it is cracked, it has thin layers of reddish brown rock with almost geometric patterning. At first I thought it was graffiti etched on it, but could see it was part of the rock.

The volcanic rock outcrops are incredibly variable. This is plain gray with some black streaks. Where chipped, there are thin layers of smooth black rock that again had me thinking maybe “lichens”.

Just one of the arroyo’s really cool volcanic rock formations. The arroyo's geology seems very different from other places in the area that I've visited and it peaked my interest to want to learn more about it.

For a full inventory list of this month's plants and lichens (with family, latín name and common names in both English and Spanish), visit this page.

Wow, another month has flown by. The local weather is still cool and pleasant with the occasional hot spell so typical of February and March here. Some of the winter bloomers are still going strong while others are are beginning to fade out. But Spring is almost here as I write this, and with the days soon to be heating up we’ll have a whole new set of plants in bloom. Until next time, hasta pronto...!

Debra Valov — Curatorial Volunteer

References and Literature Cited

iNaturalist. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. (Accessed January 2024)

The Lichen Consortium. Lichinella granulosa. https://lichenportal.org/portal/taxa/index.php?tid=125426&taxauthid=1&clid=0

Rebman, J. P., J. Gibson, and K. Rich, 2016. Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California, Mexico. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History, No. 45, 15 November 2016. San Diego Natural History Museum, San Diego, CA. Full text available online.

Rebman, J. P and Roberts, N. C. (2012). Baja California Plant Field Guide. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. Descriptions and distribution.

Valov, D. (2020). An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Mulegé, Baja California, Mexico. Madroño 67(3), 115-160, (23 December 2020). https://doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-67.3.115

Wiggins, I. L. (1980). The Flora of Baja California. Stanford University Press. Keys and descriptions.