BEE JUNE 2013

Rattlesnake – Racing against the clock – Unexpected visitors – Plant walks – Plant Inventory Stats – Bye-bye Mulegé – Hello Guerrero Negro and Bahía de los Ángeles

Mulegé, BCS — mid April to mid May 2013

A person can only take so many photos of the same plants and flowers before the computer hard drive explodes. So, to satisfy my photographic need and cut down on the number of photos I take, I’ve been playing with light to show off my beloved plant species in a new way, mainly using the spot meter to capture the flowers and leaves backlit or spotlighted by the sun. So, to get to the point here: one hot April morning while walking around one of my old haunts at Punta Arena, I saw my chance to take a photo of a Passionflower (Passiflora palmeri) glowing in the sunlight against a very dark, shady background and headed right on over.

Passionflower, Sandía de la pasión (Passiflora palmeri), an endemic to the peninsula.

You´ll find out why this is not the quality of photo I was hoping for.

Just before I reached the plant, an incessant, unfamiliar buzzing started up. It took a few seconds for the noise to register and filter down through my gray cells, reach the reptilian brain, and evoke a startle reflex, followed directly by a leap backwards. My reaction was delayed, I think, because it sounded more like a cactus wren (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus) warming up for a long song than the only other rattlesnake I’d ever heard in person. That one was more like pebbles being shaken inside a stiff paper bag, and caused everyone’s hair, including the cat’s, to immediately stand on end. Not a wren, definitely not a wren.

After I'd pinpointed the snake’s location and determined that it wasn’t going to be able to strike from behind the dead shrub under which it was taking cover about 2.5 meters away (a Sweetbush, Bebbia juncea, by the way), I moved a little closer for a better view and zoomed in on it with my camera. As it started to move out from behind the shrub parallel to me towards deep cover, I was able to see the entire body: about 1 meter long and at least as thick as my wrist at the widest point. Unfortunately, it was taking refuge under my passionflower!

Red Diamond Rattlesnake (Crotalus ruber), a species widespread on the peninsula. They are short and thick.

Can you find the body and tail? The thick body tapers abruptly to a thin, black and white striped tail tipped with the rattles.

Evidently having decided that I wasn’t a threat, it had settled down with its head deep underneath the shrub, facing away from me, but with the body and tail partially visible. At that point, I was able to angle over to the other side of the shrub (keeping the snake in the corner of my visual field) and get a few zoomed shots of the flowers and the gorgeous markings on the snake’s back. Fortunately, this beauty did not live up to its reputation as being aggressive. All of the rattlesnakes we’ve seen here have generally stopped to assess the situation then slowly moved away. In this case, the snake gave me ample warning when I was a safe distance away and moving tangentially past it.

In the 24 years we’ve been traveling to Baja California we’ve only come across five rattlesnakes. All but one was, like this one, a Red Diamond Rattlesnake (Crotalus ruber) and several were crossing the road at a safe distance. This was the first close contact for me in the 12 years I’ve been wandering in the scrub botanizing, mainly because most snakes are hibernating during the colder weather, coinciding with our time in Mulegé. It certainly gave me pause about going out alone, and put a damper on my enthusiasm while on outings during our last week in town. The temperatures had risen dramatically in late April and the critters were obviously becoming active.

Racing against the clock — El Ojo and River

After checking my "collection to-do list" one morning, I saw that I still hadn't collected a particular grass I'd seen in the middle of the river, so I made sure to put the rubber boots in the car before setting out. The plan was to reach a tiny gravel bar in the river just near the Ojo where the clump of grass was growing heartily. Donning my boots, grabbing a stray stick to help with balance, and slinging my camera over my shoulder, I set out to reach the plant. I’m lucky I’m still not stuck in the middle of the river.

After checking my "collection to-do list" one morning, I saw that I still hadn't collected a particular grass I'd seen in the middle of the river, so I made sure to put the rubber boots in the car before setting out. The plan was to reach a tiny gravel bar in the river just near the Ojo where the clump of grass was growing heartily. Donning my boots, grabbing a stray stick to help with balance, and slinging my camera over my shoulder, I set out to reach the plant. I’m lucky I’m still not stuck in the middle of the river.

The river bed looks deceptively solid from above, but is more like a layer of fine silt suspended in the water and about half a meter deep. So what appears solid gives way as you step in. After a wobbly start on the freshly churned bank, I managed to cross a solid patch of rock and gravel, then follow the opposite, firmer edge of the stream along the wall of Arundo, stepping from one small rock to another for most of the way. But then I came to a gap in the rocks, and when I put my foot down, that’s when I discovered there was no bottom any time soon.

I sank down to my shin before I stopped myself, and slowly retracted that foot, thankfully boot and all. If it weren’t for the stick, I think I might have gone over and in! Somehow, I found a solid place to cross the gap and reached the gravel bar. I quickly took photos and specimens, because as I was standing there, I was slowly sinking into the riverbed. Childhood memories of jungle movies and quicksand flashed in my head momentarily. When I turned around to retrace my path, I could see little clouds of silt from my footsteps still suspended in the water.

The reward was specimens of Rabbitsfoot grass (Polypogon monspeliensis, Poaceae), an annual weedy species that grows in damp places like stream and pond banks. This was the only plant along the entire river.

About half way to the grass

Goal reached, specimen collected, & returned safely to shore

Rumex sp. (Lengua de Vaca, Polygonaceae)

I have finally been victorious in my race against the goats and other ruminants. While showing friends the Ojo one afternoon, I saw that a Rumex had bolted and was finally blooming. There was also a large patch right along the river bank in good, unbrowsed state, though not yet blooming. We were short on time, so I delayed collecting a specimen, telling myself I’d return the next day. I didn’t make it until the second day. My heart sank when the first thing I saw was a newly "mowed" path to the river bank and then a bare patch along the river bank, the Rumex once again having been weed-whacked to nubs. I quickly looked at the place where the other plant had been blooming and to my relief it was still there, safely protected by a tight cluster of young tree tobacco plants (Nicotiana glauca, Solanaceae) that had hidden it well. Rumex inconspicuus is the tentative ID.

Dock (Rumex inconspicuus?)

Dock (Rumex inconspicuus?)

Closeup of inflorescence.

Closeup of inflorescence.

Unexpected Visitors

Just before we left Mulegé for the north, we had the pleasure of connecting with friends from California who were in Baja California to visit the cave art in the Sierra San Francisco on a 7 day mule trip. They have talked about visiting for a number of years, and finally we were all in more or less the same vicinity at the same time. From San Ignacio, where their group was gathering for the excursion, they drove two hours south to go on a plant and bird walk with us. Alan Harper is a talented photographer and birder, so I felt that the Ojo might be the perfect place for him to look for one of the peninsula’s six endemic bird species, the Belding's Yellowthroat (Geothlypis beldingi). Sula Vanderplank is a botanist working on the flora of the California floristic province in the (northern) state of Baja California. Both also work together on land and habitat conservation through TerraPeninsular, which Alan founded.

After meeting them on the highway, I led the way up to the Mulegé mission, and the mirador, a vista point hewn out of a volcanic plug that overlooks the river. It offers a sweeping, iconic view of the Mulegé oasis. I wanted them to see from above where we would soon be in the palm oasis at the Ojo.

Alan photographed the Magnificent Frigate birds (Fregata magnificens) that ride the thermals near the mirador, swooping down now and then to skim the surface for a mouthful of fresh water. While looking down at the river, we even spotted a gigantic freshwater turtle (slider of some kind) sunning on the surface.

Fortunately for us all, the high temperatures of the day before had subsided.

We were able to enjoy our time under the shade of the palm canopy with a cool breeze fluttering through the trees.

While at the Ojo, we met a man who was digging up the roots of Yerba Mansa (Anemopsis californica). We started chatting and he said that he was going to make a tea for his daughter, who had just broken her arm in three places. He said the tea is used to “cleanse” the blood and strengthen one’s system. Very soon, our entire group was gathered around as he talked about the benefits of the plant and also of Nicotiana glauca as a poultice for, among other ailments, stomach problems. By the time we finally said our goodbyes, we had established who we all were and where we came from, what relatives of his we knew, and what friends we had in common. Así es aquí (that’s the way it is here). It's so satisfying to connect with local people and share knowledge of their environment with them.

While at the Ojo, we met a man who was digging up the roots of Yerba Mansa (Anemopsis californica). We started chatting and he said that he was going to make a tea for his daughter, who had just broken her arm in three places. He said the tea is used to “cleanse” the blood and strengthen one’s system. Very soon, our entire group was gathered around as he talked about the benefits of the plant and also of Nicotiana glauca as a poultice for, among other ailments, stomach problems. By the time we finally said our goodbyes, we had established who we all were and where we came from, what relatives of his we knew, and what friends we had in common. Así es aquí (that’s the way it is here). It's so satisfying to connect with local people and share knowledge of their environment with them.

Our visit with Alan, Sula and their friends was much too short and rushed, but we managed to squeeze a lot into a few hours before they had to head back to San Ignacio to prepare for hitting the trail the next morning. Unfortunately, we didn't see a Belding's Yellowthroat. You can see photos of their trip here.

Plant Walks

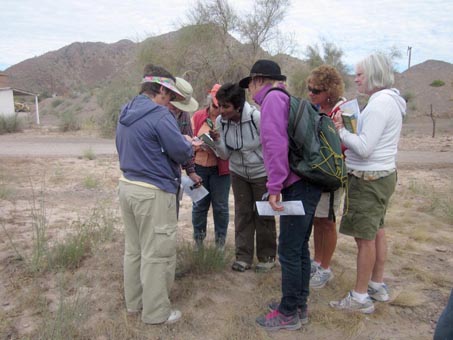

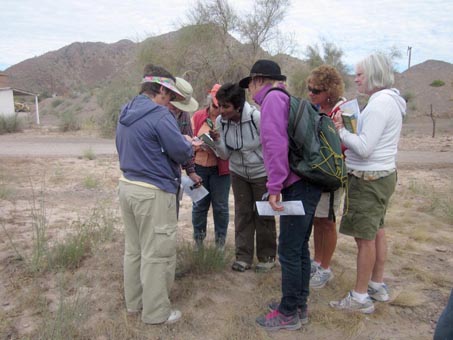

I've not yet mentioned the plant walks I lead here for English-speaking visitors and residents. I’ve been offering free, weekly guided walks when I can around Mulegé and Bahía Concepción since 2007. I prefer to call them strolls, because too many people think we are going to go on a hike. Silly them! Little do they know that they’ll be lucky if we cover 100 meters. There are so many plants out there, and I want people to learn to really see and distinguish the plants, and to ask questions about what it is that they are seeing, so we rarely get very far unless I have a certain area I want to make sure to cover.

Each week I like to go to a different site to see a different habitat or variety of desert scrub. These include the Mulegé valley, the Mangroves along the river near the mouth, the volcanic plug that is home to the lighthouse, nearby beach dunes and the Ojo, among others.

Mulege Valley desert scrub: hand lenses are a must to visualize the many minute flowers that are common with desert plants.

Extensive and well-vegetated dune system to the south of town. This dune is about 15 meters high.

Near Playa Escondida, Bahia Concepcion: the group smells the foliage of an Elephant Tree (Bursera microphylla).

Up on the dunes: we check out common desert species as well as a few that are exclusive to the dunes.

This year, I led eleven different walks between December and April. I’m hoping that next season I can spark some interest in the local Mexican residents to join me on walks. We’ve made some good connections so far this year, and next season I will have to continue to nurture them.

When we arrived after the hurricane and flood, I was already thinking ahead about the extended season for plant walks that would result. But due to unforeseen events, I missed most of December and all of January while recuperating from a fall and injured shoulder. It was a real shame, since that would have been the perfect time to see a lot of plants with leaves, and then follow them through flowering and into their dormant state by March or April.

Mulege lighthouse (Faro): the top of the trail offers a sweeping panorama of the river mouth.

When Mr. Hofmeister meets Hofmeisteria fasciculata (Asteraceae), happiness ensues. Plant walk at the Faro.

Final Stats for Year on Plant Inventory

When we left for Mulegé in late 2012, I had 329 species on my plant inventory. I ended my stay in May having added 42 more, for a total of 371. The number added represents 11% of the overall flora so far collected in the area. And there I was before we left for Mexico, not knowing about the summer rain or the hurricane, thinking that I’d likely have an uneventful field season and be lucky to add five taxa to the list.

It’s not surprising that the vast majority of plants collected were found along the river course in the palm orchards. First, I probably spent 90% of my time monitoring those areas (because of my shoulder), rather than wandering farther afield in the desert scrub that hadn’t shown much activity throughout the winter months. And second, there was a tremendous amount of water that flowed down into the valley and left standing water in a few places in the palm orchards that persisted for several months. About 80% of the taxa that I collected this year are included in the inventory of the flora of the Sierra de la Giganta ecoregion and many of these show a strong or even exclusive affinity to moist habitats, such as river banks and pond edges, habitats which don't occur within my study area except for in the palm orchards. It seems as if seeds of these species were swept downstream and found a suitable habitat, or a seed bank already existed within this habitat and sprang to life when the right conditions presented themselves this Fall, or a combination of the two.

I’m not expecting such a busy field season next year, but then ¿quién sabe? I’d love it, but will not wish on the town’s people the conditions necessary for it. Maybe I’ll be lucky and there will be new species that didn’t sprout this year but will next year.

Lush growth of Shrubby Fleabane (Pluchea symphytifolia, Asteraceae). The herbage is glandular and smells faintly minty.

Correction: This was originally keyed as Verbesina peninsularis (Asteraceae), but the correct determination is Verbesina encelioides subsp. encelioides, a weedy species not particularly common in the Mulegé.

Correction: This was originally keyed as Verbesina peninsularis (Asteraceae), but the correct determination is Verbesina encelioides subsp. encelioides, a weedy species not particularly common in the Mulegé.

The fruit (pictured at right) is quite different than the typical agricultural sunflower. It has a wide, corky margin surrounding the black body, and two bristles on each side of the notch at the top.

Flowers of Pluchea symphytifolia. Known in parts of Mexico as Lengua de vaca (cow's tongue).

Capitulum of Verbesina encelioides subsp. encelioides. Honey bees, paper wasps and butterflies were always busy feeding on them.

Adios Mulegé, Saludos a...

We sadly said goodbye to Mulegé on May 3rd and headed northward on our first leg towards Guerrero Negro, the northernmost town in the state of Baja California Sur. It sits right at the 28th parallel and the state border. We bid adieu to the crazy weather on the Gulf and headed into the cool, Pacific fogbelt. From steam room to wool socks in just 4 hours!

Fog at the mouth of Bahía Concepción, seen from inside the bay. It would appear, disappear and reappear within minutes.

View out the hotel window our first morning in Guerrero Negro. Where's the car?

Some visitors to Guerrero Negro have been known to refer to the town as the armpit of BCS, but there are an amazing array of cool things to see and do if you have the time and inclination. It's all about subtlety. Guerrero Negro is located on a windswept, relatively flat, coastal plain with parts of the town actually below the marine water table, and is shrouded in fog much of the year. So there are no spectacular desert landscapes to wow the visitors, or warm beaches to lure the sunbathers.

But sunsets over the gigantic ponds of concentrated residue (los amargos) from the saltworks provide a spectacular show almost year round. Low, sparsely vegetated, inland sand dunes as far as the eye can see appear monotonous and devoid of actual living organisms, but hide an amazing variety of plant life—especially January to March after ample fall or winter rains, when the wildflowers can carpet the dunes in shades of pink and yellow for miles.

Los amargos, huge ponds of residue from the salt evaporation process. The color of the water is reminiscent of that of a shallow tropical sea.

Active dunes to the north of the town of Guerrero Negro along the edge of Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Scammon's Lagoon). The system is extensive and very active. The sand is very fine.

The plain is also the ancestral home of the endemic Pronghorn antelope, known as the Berrendo, and there is a captive breeding program in the Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve, with a reintroduction station right out of town. And then there are the ever-shifting coastal dunes and barrier islands bordering the enormous Laguna Ojo de Liebre, one of the California Gray Whales winter breeding grounds, that are a too well-kept secret. Most dunes and shoreline are accessible by kayak while some areas have road access. You can read more about Baja's friendly whales and whale-watching on this page.

We managed as usual to have an enjoyable stay there with a friend whose sister runs a small hotel behind his restaurant, La Espinita, located just north of the 28th parallel and the state border. He is working on his Bachelor’s in alternative tourism at the local branch of the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS), so we are often lucky to get to attend a class or event whenever we visit. This time, we went to the kayaking class on the lagoon. The group is learning both to kayak and to run a small kayaking eco-tour business, offering short trips for local families and visitors on the weekends along the canals or out on the lagoon.

The class entering the lagoon and heading across to the other side where there are dunes and a mud flat. They paddled around while I investigated the marsh.

Marsh with Saltwort, Saltgrass (Distichlis littoralis), Pickleweeds (Arthrocnemum subterminale, Salicornia bigelovii & Salicornia pacifica, Amaranthaceae).

Salt marsh vegetation around the edge of the lagoon. Cord grass (Spartina foliosa, Poaceae) in the foreground and mostly Saltwort (Batis maritima, Bataceae) above that. Dunes in the distance.

Two other common saltmarsh plants are Yerba Reuma or Alkali Heath (Frankenia salina, Frankeniaceae) pictured above, and Seablite (Suaeda esteroa, Amaranthaceae).

We also met up with friends, one a botanist from the local branch of the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste and the other a local birding expert, to take a little outing one afternoon to see what the plants were up to, and to help clarify some local plant IDs. We were treated to a surprise flowering of an endemic Barrel Cactus, a few rain drops and a wonderful rainbow against a blackening sky. Later that evening, we watched the thunder and lightening and listened to the rain pelt the roof for a few minutes. We apparently were just at the edge of a storm that hit most of northern Baja California and extended up the coast well into California. Guerrero Negro is, sadly, at the juncture of the winter and summer rain patterns and so only gets a little from each if lucky.

Biznaga or Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus fordii, Cactaceae)

Biznaga or Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus fordii, Cactaceae)

These have to be the smallest barrel cacti (Ferocactus fordii) we've ever seen. This one stood about 25 cm H, and it was a large specimen! Some were only 10-12 cm D.

Northward, back to the Gulf

After leaving Guerrero Negro, we headed north about 200 km then east about 70 km, back to the Gulf coast at Bahía de los Ángeles. The day was cool when we left and there was a damp, westerly wind that had the temperatures in “Bahía” in the low 70’s. We were surprised, as it’s commonly scorching by early May.

We stopped along the way to walk out into the scrub to botanize for awhile. We saw two species of endemic Cholla cacti in bloom, Clavelina (Cylindropuntia molesta) with it’s brownish orange flowers, and C. calmalliana, with pale yellow flowers. The Coastal Agave (Agave shawii) was blooming magnificently. Interestingly, here the cardón cacti (Pachycereus pringlei) hardly had a bud showing.

Coastal agave (Agave shawii) on left, Cirios (Fouquieria columnaris) right and background.

Coastal agave (Agave shawii) on left, Cirios (Fouquieria columnaris) right and background.

Palo Adán or Tree Ocotillo (Fouquieria diguetii) in all its splendor.

Palo Adán or Tree Ocotillo (Fouquieria diguetii) in all its splendor.

The corridor from the transpeninsular highway to the Gulf is a great place to see all three species of Fouquieria (in the Fouquieriaceae or Torchwood Family) growing side-by-side: Palo Adán (F. diguetii), Ocotillo (F. splendens) and Cirio or Boojum Tree (F. columnaris). Palo Adán is near its northern range in this area. Ocotillo and Cirio both extend south several hundred kilometers to the northern slopes of Volcán las Tres Vírgenes just north of Santa Rosalía.

Ocotillo, Palo Adán & Cirio (L to R: Fouquieria splendens, F. diguetii, F. columnaris, Fouquieriaceae).

Cirio, Ocotillo & Palo Adán (L to R) occur together along this stretch between Hwy 1 and Bahía de los Ángeles

We were blown away by the magnitude of the Palo Adán in bloom. In one valley as we neared Bahía, the bajadas that entered the valley on both sides of the highway were aglow from the red torches atop the trees, creating a wide swath across the valley from our vantage point in the car. With very little traffic on the highway in either direction, we would just stop in the road so I could take photos. If that wasn’t enough, we soon came upon an area where the elephant trees (Pachycormus discolor var. pubescens, Anacardiaceae) were also getting into the swing, so it was red and dusty rose on all sides.

Palo Adan (Fouquieria diguetii).

Clavelina (Cylindropuntia molesta, Cactaceae) in flower.

The End is Near

We haven't finished our trip, but sadly I have reached the end of the entries for my Notes from the South for this season. As we continue north from Bahía, we'll pass through the Central desert and adjacent areas of Coastal Desert Scrub, then finally enter northern Baja's California Floristic Province about 200 km south of the border. If you're interested in reading more or seeing images from the Central Desert, check out my May 2010 entry. We don't expect the countryside to be as green as it was that year since it's been a somewhat drier year.

I hope that you have enjoyed reading about my/our activities as much as I've enjoyed writing about them, and have learned something new about the amazing Sonoran Desert of Baja California and Baja California Sur. I look forward to seeing you at the Garden soon. ¡Muchísimas gracias!

—Debra Valov, Curatorial volunteer