This section contains entries about our botanizing in Baja California written for the UC BEE (Oct 2012 to Aug 2021)

and The UC Hive (2022-), monthly newsletters for volunteers and staff of the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden.

Click on any photo for a larger image.

BEE JUNE 2014

Northward bound: Wind and Flowers in the Vizcaíno Desert

On our trip from Mulegé to Guerrero Negro this week, we saw more of the progression of the flowering wave of Palo Verdes (Parkinsonia microphylla and the occasional P. aculeata or Palo Brea). See last month's entry for more on that. The rest of the countryside was dark–black, brown and gray tones–and appeared slightly scorched, with the occasional flaming yellow tree jumping out at us. And here and there along the way, the subtle purplish and white flowers of the Palo Fierro or Desert Ironwood trees (Olneya tesota) highlighted the landscape.

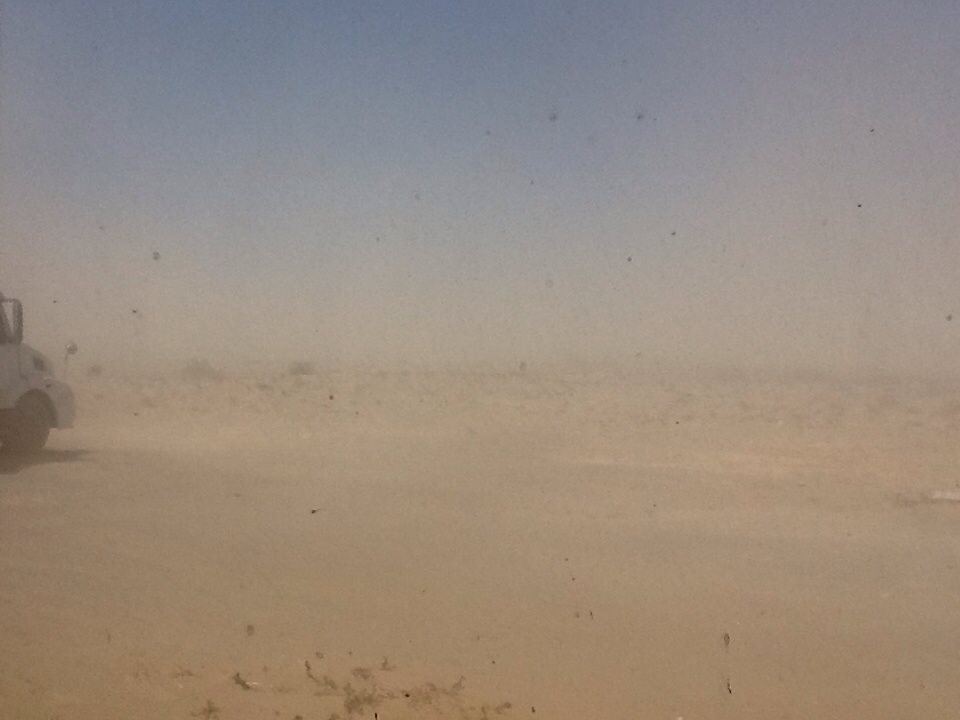

The Vizcaíno plain also appeared to be very dry and inactive. No annuals between the shrubs or along the roadsides, where it´s common to find a rich diversity of opportunistic plants. The winds were blowing very briskly across the plain from the north by the time we passed the town of Vizcaíno, where it was still 98 degrees at 6:30 pm, and entered an area of inland dunes and desert scrub. The sky was yellowish from the fine marine sediments suspended in the air. Ick! We had missed the worst of it: 3 days earlier the wind was blowing so hard that visibility was almost zero and driving was extremely dangerous on the narrow highway.

Sand storm Apr. 29, Guerrero Negro (photo: Francisco Grado V.)

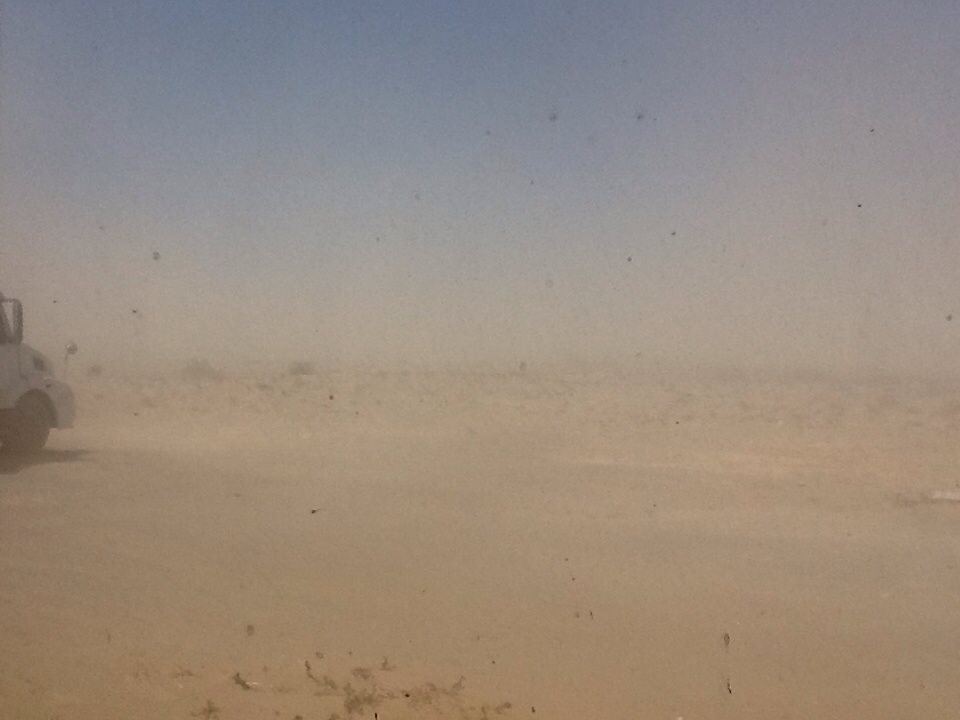

Sand blowing across the transpeninsular highway. Taken late in the day on our trip, the low angle of the sun brings out the color of the dirt suspended in the air.

It was a few days before the wind died down and the temperatures dropped enough to make an early morning walk on the plain near our lodgings attractive enough to get out of bed. At this time of the year, from the highway or at some distance, the vegetation appears to be dead or dormant. But getting up close and personal, I was again amazed by how much life there is even in the bleakest appearing environments.

The area is just a few meters above sea level and only about 2 km from the edge of Laguna Guerrero Negro. It is mostly composed of sandy, silty marine deposits with mini dunes formed by the accumulation of sand around the low, halophytic shrubs. However, every so often, there´s a deeper depression where plants are able to get a foothold because they are a little better protected from the moving sand, and they create densely vegetated hummocks (image below right).

Sandy area of very tiny dunes on Vizcaíno Plain near Guerrero Negro, BCS. Most of the shrubs are Yerba Reuma or Palmer´s Frankenia (Frankenia palmeri, Frankeniaceae) and are less than 40 cm H.

Hummock with dense vegetation. In foreground, Milkweed (Asclepias subulata) with flowers. Gray shrubs are primarily Yerba reuma with Frutilla (Boxthorn), Chamizo (Saltbush) and lots and lots of puffy gray fruticose lichens packed onto the branches of the shrubs.

The entire area is dominated by halophytic (salt-loving or salt-tolerant) plants. Many of the species have similar growth habits: they are low, rounded, densely packed and have gray-green vegetation, with either leathery and scaly, or succulent leaves.

Frankenia is by far the dominant plant. It is followed by an endemic saltbush, Atriplex julacea, which is usually a low, rounded shrub with incredibly inconspicuous leaves. The first time I saw the plant, I was fairly new to botany and thought I had been doing pretty well keying plants, but I couldn´t even tell what parts of the plant I was looking at! The leaves are scalelike and so densely packed that they don´t say "Hey, I´m a leaf!" Not until I was shown them under the dissecting microscope at the San Diego herbarium did I learn what the leaves looked like.

Frankenia palmeri shrub slowly being covered by sand.

Atriplex julacea, Chamizo, an endemic shrub.

Atriplex julacea, Chamizo, an endemic shrub.

Tiny flowers of Frankenia palmeri, measuring about 4-5 mm D.

Closer view of the dirt-encrusted branches of Atriplex julacea. The scalelike leaves clasp the stem tightly and are more visible here on the thinner branches. The rounded bulges are the staminate or pistillate flowers that consist of either stamens or style and are covered in scale-like bracts. The plant is wind-pollinated.

There are four other prominent/dominant shrubs in the area:

1. Lycium brevipes. (Frutilla or Boxthorn, Solanaceae), usually a small, low or wind-prostrated shrub with rigid, spinose branches;

2. Suaeda nigra (Quelite salado or Chamizo; Seablite or desert seepweed, Chenopodiaceae);

3. Allenrolfea occidentalis (Chamizo or Iodine Bush); and

4. Atriplex linearis (Chamizo or slenderleaf saltbush, Chenopodiaceae).

As you can see, Chamizo is a popular common name and is used for a large number of both related and unrelated shrubs on the peninsula!

Habit of Slenderleaf saltbush. The shrubs in this windswept terrain are mostly under a meter tall and are wide and low to the ground. They are dioecious and flowers are wind-pollinated.

While in this and other areas of the peninsula's Pacific side, Seablite (Suaeda nigra) is usually a low, rounded and compact shrub, here is an irregular, openly branched specimen. The leaves are often brightly colored, from green to any shade between orange and purple.

Like in many Atriplex species, the leaves of Slenderleaf saltbush are covered with pale grayish scales that are actually salt-secreting bladders (inflated hairs). They sequester salt ions and when full, pop open to release the salts and prevent internal salt toxicity. The hairs serve a dual purpose: their pale color reflects sunlight, reducing the internal temperature of the leaf.

The leaves of Seablite are quite variable in size, shape, color and hairyness (glabrous to glandular). DNA testing has shown that what looked like at least 3 or 4 different species on the peninsula are actually one. The yellow structures are the anthers. The flowers are bisexual and lack petals.

In the winter and early spring, the ground between shrubs and along the edges of the road is often densely covered with the non-native, annual iceplants known here as Hielitos that belong to the Aizoaceae family. Crystal iceplant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) is by far the most wide-spread and dominant of the two and gets its name from the easily visible, fluid-filled vesicles covering all of its surfaces that glisten in the sun and sequester salts to help the plant with deal with salt toxicity and water exchange in the saline soils. It has flat, spatulate leaves and white flowers that are about 1.5 cm D.

M. nodiflorum (Slenderleaf iceplant) is a much more delicate annual with smaller, cylindrical leaves and yellowish flowers. While it too has vesicles, they can only be seen under magnification. Both species attract bees, wasps and butterflies. Young plants are usually green, but as they age the leaves turn red, rusty or even purple. The calyces of Crystal iceplant are often magenta.

Crystal iceplant (left), has the larger, feathery flowers and flat leaves, while Slenderleaf iceplant (right) has small, yellow flowers.

Live-for-evers are abundant at least across this section of the Vizcaíno desert and at the time of this entry, are flowering madly.

Live-for-ever or Siempreviva (Dudleya acuminata, Crassulaceae) flower stalks peeking out of the remains of a Frankenia shrub.

Where there are small, concentrated populations, the rosy inflorescences stand out against the monotone dunes.

There are a number of other perennials or shrubs that, while common, are not as abundant. Two of these that currently have a few flowers are endemic to the area: Malva (Sphaeralcea fulva, Malvaceae) a perennial to shrubby globemallow with pale pink flowers; and Bahiopsis microphylla (Asteraceae), a rounded shrub with 1-1.5 cm D flowers with yellow rays and maroon stamens.

Malva (Sphaeralcea fulva, Malvaceae)

Bahiopsis microphylla

There are very few annuals at the moment, but I did come across a couple of pockets protected from the wind where two common composites were happily blooming.

Manzanilla (Boeberastrum anthemidifolium, Asteraceae). While very pretty, this is a little stinker due to the oil glands on its herbage. Relative of Fetid-marigold. With Crystal Iceplant and orange globemallow.

Desert dandelion (Malacothrix californica) is common from the Vizcaíno Desert and northward into southern California. It is a low annual, less than 40 cm, and the flower is up to 22 mm in diameter.

Manzanilla (Boeberastrum anthemidifolium), with orange globemallow (Sphaeralcea ambigua) in the background. The small, clearish bumps on some leaf tips and phyllaries of the left bud are glands.

The plant is scapose with leaves in a basal rosette. The Jepson treatment says that it is more commonly yellow than white, but here in Baja, so far I´ve only ever seen white flowers with the yellow or occasionally yellow and red centers.

This area is most definitely a "zona de neblina" or "fog zone", where a great deal of the moisture that is captured by plants comes from water vapor in the air in the form of heavy dew or fog. Our second night here, I forgot my plant press outside and in the morning, I found that the edges of some of the cardboards were soggy. This area is very much like the San Francisco Bay Area's fog-belt in terms of prevalence of fog, night time temperatures and humidity. Whenever we stay here, I feel right at home, as if I never left the East Bay!

When I took that early morning walk out onto the plain and discovered all those hidden flowers I mention above, I was surprised at how spongy and moist the balls of lichen on the shrubs were when I reached down to touch them. Even the crustose lichens along the branches were damp and soft.

On the walk, I came across what may be four different lichen species. Two were fruticose, with one of them being a "typical" shade of green for a lichen and the other gray to black. Both were ball-like, but the gray lichen was particularly adept at wedging itself into the branches, creating a very dense layer, a beard even, on the outer parts of the shrubs.

The crustose lichens were orange and olive green. They may be the same species in different stages or separate species. As we head north, maybe we'll stop to revisit a particular area about an hour away where, when viewed from near ground level, miniature forests of fruticose lichens coat the rocks and boulders overhead.

Globose, fruitcose lichens growing on Lycium brevipes.

Mass of dense, grayish fruticose lichens on Lycium brevipes, with another of the globose green lichens in the foreground, center.

Globose, fruticose lichen on Lycium brevipes. The tangled growth in the background is from the gray/black lichens.

Orange crustose lichens coating branches of Frankenia palmeri.

Well, I'll leave you with these striking images of today, May 7th, the day the wind returned to Guerrero Negro full force. Hasta luego and hold on to your hat!

Debra Valov—Curatorial volunteer

Now you see it...

and now you don't. Repeat every few minutes for the next 6 hours.