THE HIVE FEB 2025

Desert microhabitats: Lichen and bryophyte hunting

If you’ve been following my recent posts, you will know that the past two or three years on the Baja California peninsula have been quite dry. There has been little summer rain and the equipatas, those short but intense bouts of winter rain, have also been absent.

So what is a restless field botanist to do when there is so little to see in terms of leaves, flowers and fruits? The spirit of exploration may even start to wane. That is unless she knows of other interesting organisms to look for, and which she may have ignored or not had time to explore during all those wet and flowery seasons when those vascular plants were thriving and demanding attention.

I’m talking about lichens and mosses, those cryptic organisms that the average person might not even notice as they go about their busy day. And I´ll throw in some ferns as well since they too are often overlooked.

I certainly didn’t pay much attention to lichens or mosses beyond a minor curiosity whenever I encountered them. But just as my interest in vascular plants blossomed under the encouragement and guidance of a number of professional vascular plant botanists, I have also had the encouragement and guidance of experts in both bryology and lichenology: Dr. Jim Shevock and Dr. Klara Scharnagl respectively. I met both while volunteering at the UC Jepson Herbaria. Jim is currently a Research Associate at the California Academy of Sciences and Klara is the Tucker Curator of Lichenology at the Herbaria. With their help, I’ve learned a great deal about what to look for and where to search when exploring the desert.

Since meeting Jim in 2010, I have collected peninsular moss vouchers for him whenever I can. I don’t have the equipment or experience to identify moss species that to me appear to be generically green, brown or black, but Jim has said that I should not worry about not being able to identify them but to just go ahead and collect specimens of whatever I see, especially if they are from a new site.

The reasoning is that even if I collect the same species again, it provides data about persistence at the same site or adds data distribution points from a new site. And I´ve seen that even though different moss species can look alike, there may be a mix of species growing near each other and so by not collecting a sample, I might miss some interesting species that could prove to be a new record for the state or peninsula. The same principles apply to lichens.

To date, I have 90 moss collections that comprise 20 identified species as well as a number of other vouchers that are still to be determined. I also have 71 lichen collections representing an undetermined number of species (many are still waiting a determination).

If you’re not sure what a lichen or a moss is, there are numerous online sources with comprehensive information, as well as some great books. For a more comprehensive explanation, this British Lichen Society page is a good start. There are many other great websites to explore. The Lichen Portal, a project of the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria, has links to photos and descriptions of lichens worldwide. In order to move on to my road adventures, here I will only briefly describe the two groups of organisms.

Lichens. At the most basic level, lichens are a stable symbiotic association between one or more species of fungi and algae and/or cyanobacteria. The fungus provides the substrate (structure) while the algae provide sugars to the fungus through photosynthesis. Fungi that form these associations are known as lichenized fungi while the algae and cyanobacteria are photobionts. Lichens may also play host to other fungi species, bacteria, yeast, protozoa and small invertebrates.

A lovely sampling of lichens from our plum tree in Oakland, showing crustose, foliose and fruticose forms.

More lichens (some repeats) from our tree. I counted about 15 species on the tree and another 2-3 other species on adjacent fence boards.

Lichens are classified and named by the fungal partner. There are several categories of lichens based on the structure of the thallus (body) and relationship to the substrate on which it grows: crustose (adhering tightly to the substrate), squamulose (composed of small "scales" or squamules), foliose (leaf-like, more loosely attached), and fruticose (with branchlike structures and 3D shape, often with a single place of attachment). See the two above images for examples.

Lichens grow on a wide range of substrates although many genera are restricted to a particular class of substrate such as rock, bark or soil. For some lichens, these classes are more refined, with lichens found only on a particular type of rock (e.g., calcareous, granitic), bark (e.g., conifers, hardwood), wood (e.g., milled boards, rotting wood); soil (e.g., volcanic, granitic) or even on concrete and other man-made surfaces.

Mosses. Mosses are bryophytes (along with liverworts and hornworts) and are classified as non-vascular plants, meaning they have no internal structures for moving water and nutrients from their base upward to leaves. Instead, the leaves, which are mostly just one cell thick, are capable of absorbing water rapidly, turning a dry, seemingly lifeless indistinguishable lump into a soft green living mat within minutes.

A small patch of moss may consist of hundreds of tiny plants, each composed of rhizoids that anchor it to the substrate, a stem formed by the bases of overlapping leaves and the leaf blades. An individual plant with numerous leaves may measure ≤1 mm H x D when dry and open to 2+ mm D when wet. See images below for wet and dry samples of the same moss.

These diminutive plants perform photosynthesis within their leaves. Mosses reproduce via spores and their lifecycle includes both a sexual and asexual reproductive stage. Here is a good place to start for more information about mosses.

A rehydrated specimen of the moss Trichostomum crispulum from the Sierra de Guadalupe (2019).

The same moss specimen as at left, before it was rehydrated (Trichostomum crispulum). Magnification c. 1/2 that of image at left.

November 2024 — Sierra de Guadalupe, Mulegé — the Hunt is On

So mid-month my friends and I set out in their 4-wheel drive buggy into the sierra west of Mulegé on a lichen, moss and fern hunt. My goal was to return to a previous site near Rancho El Rincón where, in Dec 2018, I had collected moss and ferns. At the time, lichens weren´t on my mind, but with my more recent interest piqued, I was curious to see what the slate-like cliffs and boulders might be harboring.

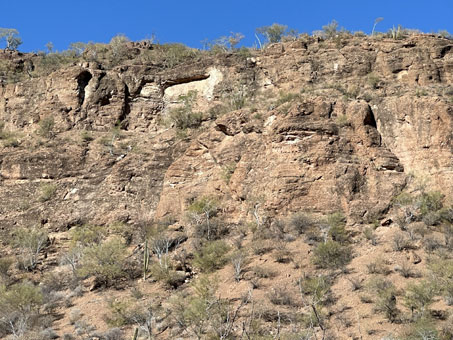

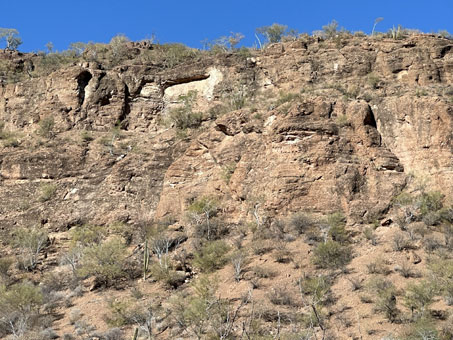

My friends pointed out the chivo (goat) rock on this cliff. Vegetation was drier than I expected given that it had rained in October. Plants in the shady, steep-sided canyons were much greener...

...as can be seen here with Palo blanco (Lysiloma candidum at center), Arrow Poison Plant (Pleradenaphora bilocularis, left) and a Gallineta (Callaeum macroptera, foreground) with fruit.

West of Rancho El Aguajito, the vegetation was quite dry. Just a handful of shrubs and trees, including Baja California Mesquite (Prosopis articulata) and Little-leaf Palo Verde (Parkinsonia microphylla), were the only green plants. Compare this to a 2018 photo in the vicinity.

If you enlarge the photo, you can see that the lack of leaves on the cliffside plants allow the Organpipe Cactus (Stenocereus thurberi var. thurberi) to stand out starkly against the blackish rock. Just west of Rancho El Rincón.

Closing in on the rock outcrop that I wanted to search for lichens. I had already found some mosses and ferns at the site in 2018.

This trip, I paid more attention to the rock types near the ranch. I saw that the gray/black slate rock (laja) forming the cliffs was extensive.

Cliff in full shade that turned out to have a lot of lichens. I didn't have much time for exploration on my 2018 trip.

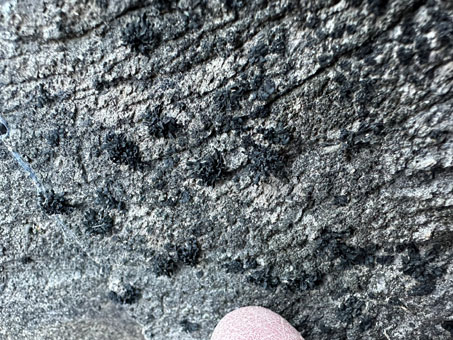

Another part of the cliff, covered with small fruticose black lichens, giving it a polkadot appearance. The rock face was cracked both vertically & horizontally.

Moss and fern habitat at the base of the cliff. I soon saw that this area was also prime lichen habitat. This type of rock is known as laja.

Laja is used for paving stones locally. This boulder is a perfect example of the slate (or slatelike) rock that shears into slabs.

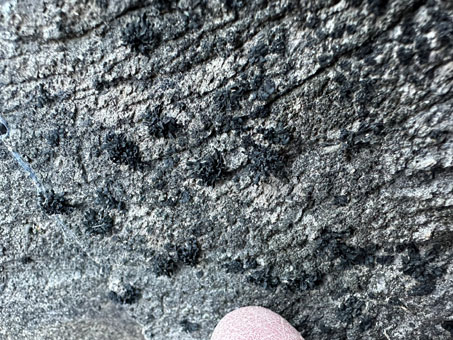

Black lichen #1.

A closer look at lichen #1 which appears to be foliose.

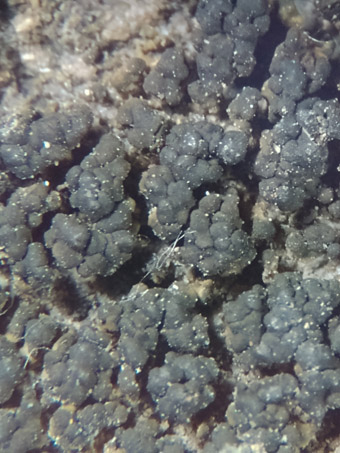

Even closer view of Lichen #1. These lichens could be found on practically every boulder on the side of the hill I was investigating. I haven't yet had a chance to upload the photos to iNaturalist or look at all these black lichens under the scope.

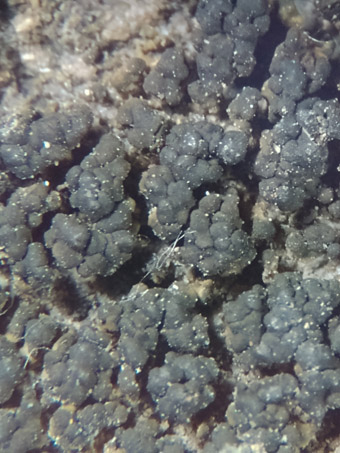

I'm calling this Lichen #2 because it has a distinct fruticose structure, growing into 3-dimensional shapes that are also easily detached from the rock. This is similar to, or the same species as, a lichen I collected in Mulegé which is likely Lichinella nigrescens.

Black Lichen #3. It differed from other black ones in that it appeared to be crustose and growing in small, discrete, circular patches about 25 mm D. It could also be a younger stage of #4 (below).

It was composed of tiny bead-like structures that could easily be rubbed off, becoming a grainy powder. Many of the clusters butted up to others to form large, irregular patches, like #4

From a distance, Black Lichen #4 looks alot like #3. But this was clearly crustose, being well adhered to the rock surface.

Lichen #4 had a somewhat greenish tinge and as can be seen, was densely packed. Its mostly irregular patches were extensive.

Lichen #4 magnified 20-30x. The surface of the thallus is composed of separate round or almost hexagonal clusters, each with a small number of rounded bumps.

Next outing, I'm bringing a hammer or pick. I was afraid I was going to break the fork on my clippers trying to pry a lichen covered rock from the cliff.

And this is Black Lichen #5. I would say this is squamulose. It wasn't associated with any other lichen. Each thallus was ±5 mm D. Rare.

To summarize, while there appeared to me to be 5 different black lichens, based only on the differing morphology that I could see with a hand lens and camera, it is quite possible that the two crustose lichens (#3 and #4) could be the same species at different stages of growth. Foliose #1 could be the same as Fruticose black #2, only at an earlier stage before it had started to branch. And who knows about squamulose #5? given that there were so few to see and collect. I am very interested to know what Klara and her students determine once they have them all back at the lab. As with the many mosses that look so similar (at least to me!), so it goes with the lichens, and this can be very challenging as well as frustrating. But the hunt is still rewarding, regardless of the final results.

I'll be interested to learn if this squamulose brown lichen (possibly a Placidium) growing on the soil is the same as the one in the next photo. Note the moss growing around and within the squamules.

If this brown lichen is the same species, the difference in appearance might be due to location and development. The one at L was in deep shade while this one was in bright but indirect light on soil and rock.

This is the first yellow lichen I've seen here in the Sierra. Yellow and orange species are common and widespread farther north in the Central Desert region and the CA Floristic Province of Baja California. It is likely Acarospora socialis. I was able to get a small sample of the lichen on a rock, with help from Javier and a sharp rock.

No clue if the greenish-black lichens between the yellow patches are the same as Lichen #4. Different species of lichens commonly grow butting up against, or even on top of each other, and dead lichen may change color so as to look like yet another species. I'll let the experts decide.

More lichens. I was able to collect the orange lichen. The greenish-white lichen may be another species.

The orange lichen is bordered by the foliose/fruticose lichen #1. First orange lichen I've seen in the Sierra.

And this is likely the 9th species of lichen we saw. Grayish-white, crustose thalli with black apothecia, each cluster to about 25-30 mm D.

As this lichen was tightly afixed to a huge rock and we had no winch, tools or desire to wrestle it into the buggy, we had to make do with these photos!

Ferns

Cheilanthoid ferns in the family Pteridaceae are found throughout the desert regions of the Baja California peninsula. Most are xeric-adapted and are remarkable in their ability to enter a period of dormancy during dry times, in which their relatively small leaves curl up, often exposing a lower surface covered with a dense, often waxy substance (farina) exuded by glandular hairs that most likely protect the leaf from complete desiccation and UV damage. They will revive when there is sufficient moisture. They share this "resurrection" ability with arid land mosses and liverworts.

Cheilanthoid ferns in the family Pteridaceae are found throughout the desert regions of the Baja California peninsula. Most are xeric-adapted and are remarkable in their ability to enter a period of dormancy during dry times, in which their relatively small leaves curl up, often exposing a lower surface covered with a dense, often waxy substance (farina) exuded by glandular hairs that most likely protect the leaf from complete desiccation and UV damage. They will revive when there is sufficient moisture. They share this "resurrection" ability with arid land mosses and liverworts.

Ferns are most obvious after spring or summer rains and are commonly found in full or partial shade in rock crevices or under rock ledges. The photo at left is of a dormant fern, Notholaena lemmonii var. lemmonii. The pale, cream colored lower surface is obvious, especially against the deep shade and the dark petioles. Another species in this genus has two varieties, one with yellow farina and the other with white.

Morphological characters like leaf shape, type of lobing, the presence of farina or scales (and their color), the color of the petiole, presence of stem scales and how spores are distributed on the leaf surface are used for identification. Following is a series of photos of the resurrection of my fern specimens. They were taken over a period of about 8 hours, starting with rehydration at 0:00 hours when they were placed on paper towels in small bowls, purified water added (tap water has chlorine) and their leaves spritzed with a spray bottle. I then covered each with a tall, clear plastic cup to keep the air warm and moist.

0:00 hours.

Pringle Lip-fern (Myriopteris pringlei var. pringlei). Note the scales on the petioles and lack of farina.

0:00 hours.

Helecho de las Piedras (Notholaena lemmonii var. lemmonii).

0:00 hrs – Myriopteris – water added

0:00 hrs – water added – Notholaena

01:25 hrs – Myriopteris

Already showing leaf response.

01:25 hrs – Notholaena

No obvious sign of reviving.

05:50 hrs – Myriopteris

Reaching peak revival

05:50 hrs – Notholaena

Mostly the lower leaves are showing recovery.

10:30 hrs – Myriopteris

Showing a few more leaves and all more robust.

10:30 hrs – Notholaena

The upper leaves finally opening; more lower leaves.

It was interesting to watch the ferns I collected more closely than I had the first time in 2018 when I collected a clump of the same species and revived them in a closed plastic box overnight as described above. Those specimens had withered after I'd collected them earlier in the day but they fully recovered. The surprise when I opened the box in the morning was worth the nightlong anticipation. See my previous Bee post for more photos of the Myriopteris in its habitat.

This time, the specimens were completely dry and the leaves brittle. I wasn't sleeping well that night so I kept an eye on them occasionally throughout the night and early morning, checking to see if anything was happening. The Myriopteris was much quicker to recover and lasted for 3-4 days on the counter before I finally had to dry them off and put them in the press. By contrast, the Notholaena was much slower to respond and didn't make such a full recovery. They also didn't last as long before starting to show signs of going dormant again and I almost missed my chance to get a good pressed specimen with open leaves.

Dry mosses on the hillside where I also collected the brown lichens. These are likely the same species I collected in 2018, but we shall see.

Closer view of one of the moss specimens. This is just a small piece about 2-4 cm D from the larger patch covering about 15 x 20 cm area.

One of the few plants I saw in bloom: Peninsular Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus peninsulae var. peninsulae), one of the 100+ endemic cacti on the peninsula.

The perianth segments vary in color, from having pale orange margins & a red midstripe to red margins with a dark red stripe. Strongly hooked spines help with ID.

Lots of green as we passed through steep canyons.

Roadside art? We stopped to ponder this...

The Seep

I've written several times about this site (May 2014, Jan 2019, Feb 2024), located about 800 meters uphill from the Vado de la Virgencita, another favorite spot (see previous links). The seep appeared to be drier this trip, though there was ample moss and a small pool. But there were fewer vascular plants species as well as fewer and smaller individual plants. Surprisingly, the small stream and shady pools were all completely absent as we passed the Vado de la Virgencita.

For previous Sierra Guadalupe trips, see: Apr 2013 (San José de Magdalena - SJdM); May 2014 (Pacific route to La Ballena); Jun 2015 (SJdM); Jan 2018 (Arroyo las Chuparrosas in southern valley); Jan 2019a and Jan 2019b (Sierra Zacatecas & Sierra Guadalupe via Pacific route); Jul 2020 (Arroyo San Nicolás & SJdM); and May 2021 (SJdM to Mulegé via ex-Misión de Guadalupe).

There were a few small Tree Tobacco plants (Nicotiana glauca) on the outer edge of the seep and the Cyperus dioicus plants dangling from above were sparser and drier than the last visit

Here we have moss pillows on the face of the road cut from which the seep emerges in several places. Stemodia durantifolia var. durantifolia (L) and Bacopa monierri (R).

The first time I visited the seep back in 2016, there was what appeared to be a Spearmint plant growing in the small pool at the base of the roadcut. Each time we returned, I looked for it, but it was no longer there.

This trip, it was back, two small stems growing out of the wall of the seep. My friends thought someone from a nearby ranch might have transplanted a sprig or two from their garden. It is a non-native garden variety.

An ample pillow of moist, cushy moss, a species I've collected before but which has yet to be identified. There are at least two species at the site, but only one has been IDed after being accessioned.

That's it for this month's entry. I hope you enjoyed looking at the desert on a more micro level. The diversity of life is staggering in a so-called "barren, hostile place" which is so often the image of deserts that people have in mind. Until the next adventure, hasta pronto...see you soon.

Debra Valov — Curatorial Volunteer

References and Literature Cited

British Lichen Society. What is a Lichen? Accessed 15-Jan-2025 at: https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/learning/what-is-a-lichen

Consortium of Lichen Herbaria (2025). Available at: http//:lichenportal.org/portal/index.php. Accessed 15-Jan-2025.

Kao, T.-T., C. J. Rothfels, A. Melgoza-Castillo, K. M. Pryer, and M. D. Windham. 2020. Infraspecific diversification of the star cloak fern (Notholaena standleyi) in the deserts of the United States and Mexico. American Journal of Botany 107(4): 658–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1461

Rebman, J. P., J. Gibson, and K. Rich, 2016. Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California, Mexico. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History, No. 45, 15 November 2016. San Diego Natural History Museum, San Diego, CA. Full text available online.

Rebman, J. P and Roberts, N. C. (2012). Baja California Plant Field Guide. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. Descriptions and distribution.

Valov, D. (2020). An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Mulegé, Baja California, Mexico. Madroño 67(3), 115-160, (23 December 2020). https://doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-67.3.115

Videos:

Syntrichia caninervis, the desert moss: bioinspiration. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKn8oFIwFg0

Dormant desert moss comes ALIVE in real-time! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHgmCpkEmrA

Biomechanics of water in Syntrichia (Javier Jáuregui-Lazo). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QyAZ8KR2PPo