This section contains entries written for the UC BEE, the monthly newsletter for volunteers and staff

of the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden, about our botanizing in Baja California, and starting in October, 2012.

Click on any photo for a larger image.

February 2014 BEE

Dec 3, 2013

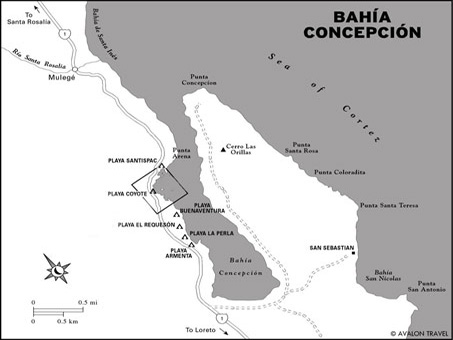

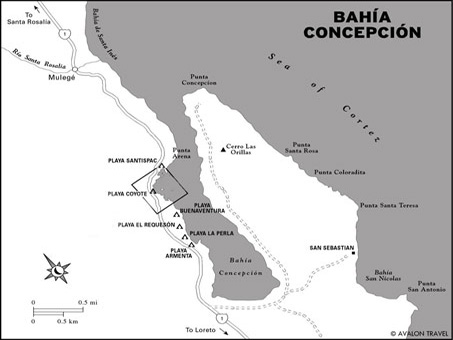

The things I get myself into sometimes! A friend invited us out in his catamaran to sail over to Isla Coyote, a small island in Bahia Concepcion. We had originally met on one of my plant walks and when we run into eachother, he always tells me about the new and interesting plants that he's unfamiliar with so I can help him identify them. He had told me that he'd seen some really interesting plants on the island, which was quite green after the summer rains. I'd never been to the island and have always wanted to go, but never thought I'd actually get there anytime. So we were eager to go.

The day turned out to be perfect for botanizing, but not so great for sailing. We ended up motoring over to the island because there was absolutely no wind. The bay was glassy and it was slightly overcast so it wasn't too hot. The water and sky were so beautiful and our time on the water was very quiet even with the cat's small motor.

View of Playa El Coyote and Isla Coyote, the large lump on the right side, in the middle of the image.

Leaving from Playa El Burro for the island. it was warm and calm and the water temperature was perfect for swimming.

Rounding the point and coming in towards the beach on the north shore of the island.

Approaching the beach. Beach grass on the berm with salt/mud flat behind and cliffs rising above to the island's saddle maybe 12-15 meters (or 40-50 ft) high.

Isla Coyote is the small dot in the center of the black square.

Image from Internet.

Coyote Island is just to the left of center in this image, about 1/2 mile or so off shore.

The island is composed volcanic lavas of various consistencies. It is well vegetated, except on the most sheer cliffs. Beach ahead.

Beach dune community with steep cliffs rising sharply out of the water.

When we got to the island and debarked first onto the dinghy and then shore, the day was starting to warm up a little and the clouds were breaking up. The clouds of mosquitos weren't so nice!

We landed on the north shore of the island, where there is a lovely crescent of white sand beach backed by a strip of mudflat (dry) with plants typical for that habitat: Allenrolfea occidentalis, Suaeda nigra, Lycium brevipes, Sporobolus virginicus, and Sesuvium portulacastrum. However, when I looked up at the cliffs behind the salt flat, I said to myself, "there is no way I'm climbing up that". I'm actually not too bad at going up, but coming down is a completely different matter and I didn't fancy slipping and sliding down the scree or off of a cliff on the way down.

Going against my better judgement, I listened to my friend who assured me that there was a fairly easy path up the slope and I wouldn't have any problem. Sure, I said. I could see that he really didn't understand my physical problems. He made several trial attempts to find the path in the dense foliage and finally decided on the best path up, one that traveled at an angle across the face of the slope/cliff. "What am I thinking?" I asked myself not for the last time as I started up after him, my walking stick clutched in one hand, the camera and water in my fanny pack. "I must be crazy," I muttered under my breath.

A good view of the loose volcanic rock in places. At least here, we weren't battling the spiny or sticky bushes trying to get us.

A little more than half way up the hill. The vegetation was so dense in places, I was afraid it would knock me down the hill.

It's a long way down there. But such an amazing view.

We finally made it to the top of the saddle.

The wand-like plant in the photo above left is a white tree ocotillo (Fouquieria burragei), a BC endemic. The flowers are white or tinged with pink. Its range begins about 10 km north of Mulege and continues disjunctly to around La Paz. It is found on rocky slopes and rocky alluvial fans. Unfortunately, the dried inflorescences at the tips look like red flowers in this image. We finally made it to the top of the saddle. I was amazed how dense it was. So much green and so much ground cover as well. The dominant plant was Matacora (Jatropha cuneata, foreground)

In all, it turned out to be a wet year, with 16 named tropical storms in the Eastern Pacific between May 15 and November 4. Three of them, tropical storms Ivo, Juliette, and Kiko, occurred during an 11 day period between August 22 and September 2, with flooding around the Cape and La Paz, and major highway washouts reaching north beyond Loreto.

Flooding across highway in vado (wash), Punta Abreojos, on Pacific Coast. Water flows fast and deep. Tropical storm Ivo, August 24.

Flashflood in arroyo bed, Santa Rosalía. The town is built in the bottom of a deep arroyo. This is minor.

Tropical storm Juliette, August 28. (Photo credit: unknown)

In September, the peninsula got a little bit of a reprieve before tropical storm Octave showed up on October 13 and stalled off the coast, dumping lots of water. This storm was probably the most damaging due to heavy rains and flash floods. In a 48 hour period, San José del Cabo registered 130 mm (5.12 inches), Loreto 205.2 mm (8.08 inches) and Mulegé 91 mm (3.58 inches).

Now, the average annual rainfall for the Mulegè area is only 30 to 70 mm (1.18 and 2.75 inches) (Rebman and Roberts 2012, Baja California Plant Field Guide).

Fortunately, Octave did not result in flooding in Mulegé, and it turned out to be the last storm to affect the town this hurricane season, though storms kept forming in the Pacific until early November and we experienced both cold and warm fronts from the instability.

While Mulegé made it through the summer unscathed, it seemed like my friends in town spent a lot of it on heightened alert. But with the experience of six major floods, three of them devastating to the town’s infrastructure and economy, they say they will no longer take these summer storms for granted and would rather be seen as being too cautious than not cautious enough.

Bridge washout south of Mulegé. Fortunately, the paved detours were as good as, or better than, the original highway. This project is a massive repair job to this fairly new bridge.

While the bridge itself held up across this huge arroyo, the roadbed connecting to the bridge washed out, leaving the pavement above appearing mostly intact, but unsupported.

October 22-28, 2012. Mulegé, at last! When we first reached the Gulf of California, and dropped down into Santa Rosalía (the first Gulf town in BCS that the highway passes through) it didn´t look very promising for botanizing. The hills showed just a little new growth for the next 15 to 20 miles. But at about 10 to 15 miles north of Mulegé, the landscape rapidly became greener. It was a perfect example of the serendipitous nature of rainfall in the desert. The town was vibrant with growth.

With all of the greenery, I was anxious to get into the field as soon as we arrived. Fortunately it was not very hot, but it was somewhat humid, and there were a lot of mosquitoes, so it was important to get out as early as possible before the bugs and humidity got us. We were up and out at O-crack-30 on only our second day in town, looking mainly for summer annuals that might still be present. Unfortunately we had some car trouble and the field trip was cut short, but not before getting lots of great photos and adding a species of Boerhavia to the checklist.

Green hills north of Mulegé. The shrubs were heavily leafed out and there was a lot of ground cover as well this season.

Spiderling. (Boerhavia triquetra var. triquetra, Nyctaginaceae)

While stranded at home the following day without a reliably funcioning car, our friend John Rebman, Botany Curator at the San Diego Natural History Museum and his field assistant John LeGrange pulled in for the night. They were on their way south to meet up with other team members of the Binational Multidisciplinary Expedition to the Sierra Cacachila (just south of La Paz) that was starting later in the week. (To see a short video trailer of the expedition, click here).

They were going to continue their trip south in the morning, but had time to do some fieldwork with us. Jon asked me if there was a particular hillside that I was unable to climb that they could botanize for me, so the next morning we set out for the Ojo de Agua and the steep rocky outcrop that rises up behind it. While the guys climbed up the hill, my partner and I hung out around the bottom looking for bryophytes and other plants of interest. We saw numerous places with biological soil crusts and the beginnings of mosses poking out. There were also lots of fleshy fungi in the very damp soil, not a very common sight in this normally arid environment.

A group of particularly large mushrooms, about 6 cm in diameter growing in the soil. The dark patches are from the biological soil crust starting to dry up.

These two mushrooms were growing out from between what looked like scales in the trunk of a fallen palm tree. Each was about 3-4 cm in diameter.

While poking around in the dense vegetation, I came across Schaefferia cuneifolia, known locally as Sarampión (translation: measles), a woody shrub with very stiff branches and small leathery leaves. Ever since I first encountered this plant about 12 years ago, I’ve never seen the flowers, only the bright red fruit that give the plant its common name. So when I came across the plant and started looking for flowers as I usually do, I was taken aback by the fact that there were actually some present. I was extremely excited to be able to get photographs as well as voucher specimens with flowers. Jon was happy to take photos too, as he said he’d never seen the plant in bloom, except on herbarium sheets.

Sarampión (Schaefferia cuneifolia, Celastraceae). This is a common shrub in the desert scrub, well adapted with small, thick, leathery leaves, and thin, intricately arranged branches. The flowers are dioecious and have 4 green petals.

The common name is quite appropriate for this plant which looks like it´s broken out in measles. The fruit are fleshy drupes which are probably eaten mostly by birds. They have just a slight bitterness to them.

Jon is a walking encyclopedia on Baja California plants and also the only person that I have met who can walk through a field of knee-high Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) and immediately pick out a few sprigs of a different grass species from the mass! Thanks to him, two more species were added that day to the inventory: Echinochloa colona (a non-native, annual grass) and the Baja California Green Violet, (Hybanthus fruticulosus, Violaceae) a native perennial herb more common at higher elevations, such as to the west of us in the Sierra de Guadalupe.

November 6-7, 2013.

We decided to make an overnight botanizing trip to Loreto, 90 miles south of us. Part of the drive is along the western edge of Bahía Concepción and then after climbing a fairly low grade at about the halfway mark, the vegetation begins to change as the highway passes into the Sierra La Giganta phytogeographic region of the Sonoran Desert. It’s a little higher in elevation, the plant cover is subtly denser and there is a lot of underground water.

South of Bahia Concepcion and north of Loreto.

South of Bahia Concepcion and north of Loreto.

Tabardillo or Pink fairy duster (Calliandra eriophylla, Fabaceae).

View of the Sierra La Giganta range north of Loreto.

Wildflowers north of Loreto.

Tabardillo or Pink fairy duster (Calliandra eriophylla, Fabaceae)

In numerous arroyos, the endemic yellow morning glory (Merremia aurea), known locally as Yuca, draped the tops of trees 5-7 meters tall. For several kilometers, the roadside was blanketed in a native species of purple morning glories (Ipomoea ternifolia var. leptotoma), and golden yellow Chinchweeds (Pectis rusbyi and P. vollmeri).

There were a number of washouts, some of them major, along the highway, signs of a lot of water having flowed down into the lower lying Central Gulf Coast desert scrub. We soon found out that there had been so much water after Octave that the aquifers were overflowing, and with a little help from a small earthquake shortly afterwards that created cracks in the aquifer, water was continuously bubbling up out of the ground in the downtown area (historically an oasis), closing a number of businesses.

Purple morning glories line the highway for kilometers, north of Loreto (Ipomoea ternifolia var. leptotoma, Convolvulaceae)

The morning glories were spectacular, especially highlighted by grasses and other wildflowers at the sides of the highway.

As I walked away from the highway into a densely vegetated wash, the morning glories were poking out of the grasses and draped on shrubs everywhere. The yellowish orange composite flowers are an endemic chinchweed (Pectis vollmeri, Asteraceae), which smells like lemon oil when crushed.

Before entering the town of Loreto in search of dry lodging and food, we continued right on by, heading south for about a half hour to an area where the escarpment of the Sierra La Giganta ends abruptly in high cliffs 0-2 km to the east of the highway. A friend who went south to La Paz in September said that the cliffs there had been boasting numerous waterfalls visible from the highway. Unfortunately by the time we visited, we couldn’t see any waterfalls, but the mountains and bajadas (alluvial fans) were thick with vines, shrubs and annuals.

Highway heading south out of Loreto. Coralvine (Antigonon leptopus) and wild cucumber draped many plants.

Densely vegetated alluvial fan from the Sierra la Giganta escarpment meets the Gulf not far south of Loreto.

Densely vegetated hillsides of Sierra La Giganta, just south of Loreto near Juncalito.

View of the Sierra La Giganta escarpment near the Gulf coast south of Loreto. Waterfalls could be seen here in September.

December 6. Mulegè is still incredibly green even now in December. The mountains around us are still quite lush and even though the groundcover is dying back, wildflowers abound and the shrubs and trees are still magnificent. We are off to Ensenada to attend the 11th Binational Botanical Symposium at UABC in Ensenada (Dec 12-13), where I will present on my Mulegé flora checklist and vegetation survey. As we headed north today, the abrupt change in the vegetation was evident within just 8-10 km north of town. It really hit me then that the town truly is an oasis and a unique place.

So, that’s it for this entry. I am going to try to add material this season on a more regular basis like a blog, in order to keep up with what’s happening currently. Feel free to check back between BEE issues because it’s been a really active couple of months and I’ve barely touched upon it here. Hasta pronto/See you soon!

— Debra Valov, curatorial volunteer